Warning: include(C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php' for inclusion (include_path='.;.\includes;.\pear') in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

HOW PEOPLE LEARN AND HOW PEOPLE LEARN LANGUAGES

UNIT 1: HOW PEOPLE LEARN

1. Education psychology theories

These might be some questions you might ask yourself while reading this first part of the unit:

* So you’re saying my student Emilio is like Pavlov’s dog?

* Why should I be interested in what psychology says if I’m sure I’ll learn how to teach Emilio by teaching him?

Education psychology theories have changed throughout the years. Back in the 1950s the ruling theory was behaviorism, which explained human and animal behavior in terms of conditioning, without appealing to thoughts and feelings; stating that people learn by modifying behavior patterns. This is where Pavlov’s dog comes in. He was given food after hearing a bell ring, thus every time he heard the bell he would start salivating, getting ready for the experience. Do you think this thoroughly explains how a person acts and reacts to stimuli? What would this be important?

In a broad sense, a learning experience can be more or less fruitful depending on conditions, and a teacher can modify these conditions systematically with some knowledge on how people learn. As a consequence, an understanding of these theories can facilitate the achieving of learning goals and objectives. In a more detailed sense…

Behaviorism states that one learns by trial and error and building connections between stimuli and responses. It strives to change external behavior through repetition of desired actions, reward of good habits and discouragement of bad habits.

In the classroom this view of learning led to repetitive actions, praise for correct outcomes and immediate correction of mistakes.

In the field of language learning this type of teaching was called the Audio-lingual method, characterised by the whole class using choral chanting of key phrases, dialogues and immediate correction.

Later, in the 1960s, the dominant paradigm was cognitivism. It focuses on inner mental activities (e.g. thinking, memory, knowing, and problem-solving) to understand how people learn. It is closely related to linguistics and defends that we learn by observing others who are more skilled or by participating in peripheral but significant tasks -e.g. listening to the language in use-.

This theory opposes behaviorism stating that people aren’t programmed animals that respond to environmental stimuli, but rational beings that need active participation in order to learn, and whose actions are a consequence of thinking. It’s not that behavior isn’t changed, but that those changes are product of what goes on inside the person’s head.

The dominant model in cognitive approaches to second-language acquisition is the computational model. This involves three stages. In the first stage, learners retain certain features of the language input in their short-term memory. Then, learners convert some of this intake into second-language knowledge, which is stored in the long-term memory. Finally, learners use this second-language knowledge to produce spoken output.

These approaches see practice as the key ingredient of language acquisition and simulations as models for ways to solve new problems as they come up.

The third and last theory we’ll study is Constructivism. Even though this theory has historical roots that date back to Socrates (around the 4th century BC) and Kant (18th century AD), it has been mainly influenced by the writings of Jean Piaget (1896-1980) and Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934), and has found wide acceptance since the early 1980s.

Constructivism places emphasis on prior knowledge, skills, beliefs, concepts and experiences of the learners, stating that all of these are social and cultural determinants that influence what they notice about the environment and how they organize and interpret it. This would mean attention needs to be paid to the incomplete understandings, the false beliefs, and the naive interpretations of concepts that learners bring to class.

According to this theory, interactions with adults, more capable peers, and cognitive tools -e.g. books- are internalized to form mental representations; which would be the equivalent to learning outcomes. In that sense, learning would be an active and contextualized process of constructing knowledge and not acquiring it.

When it comes to teaching, it entails scaffolding; in which the social information environment offers supports for learning that are gradually withdrawn as they become internalized. It also emphasizes the importance of helping people take control of their own learning; stating that they must learn to recognize when they understand and when they need more information.

2. How people process information

* What exactly is going on inside Emilio’s head while asked to match TL words with their meanings?

It is important to consider how learners will process the information that they are taught. A significantaspect of this is to look at the prior knowledge that a learner already has of the subject and related subjects. An important part of guiding learners, particularly language learners, is helping to unlock or activate this existing knowledge, which will enable them to more easily progress and take in new information. In language learning this usually takes the form of making repeated references to points already studied, as part of exercises on issues that are new for the learner. The language teacher must also elicit answers and information from the learner and encourage them to access their prior knowledge, rather than ‘spoon-feeding’ answers or allowing learners to decide prematurely that they ‘don’t know’ or ‘don’t understand.’

* How come Emilio practically never remembers the TL from the previous class? What can I do so he does?

Learners process information in a different way if they associate that information with a particular idea, image, sound etc. We know from every day experience that it is much easier to recall information that we associate with a strong memory; something that had a big impact on us or impressed us in some way. In language teaching this concept can be used to help learners fully comprehend and truly learn an element of language. Teachers can use strategies such as visual aids, creative use of sound, the use of realia – real objects, the sight and feeling of which students will then associate directly with their names. Strong links are then formed in the learners’ brains and information is more easily retained.

3. How people retain information

Mnemonics refers to techniques that enhance the capacity to remember pieces of information. These techniques can be used by those who need to memorize large amounts of information, such as medical students and also by language students, in order to memorize vocabulary and structures. Below is an example of Rhyme Mnemonics:

I before E except after C

or when sounding like A

in neighbour and weigh.

Mnemonic techniques usually aim to translate an abstract, impersonal piece of information into something more interesting and perhaps surprising, which the brain will more easily remember.

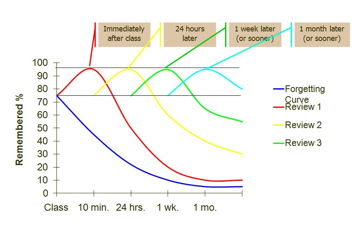

If thinking about the cognitive computational model, a key aim of language learning is to transfer information from the short-term memory to the long-term, therefore ensuring that it is retained for an extended period of time. A student may appear to understand a particular point when it is first taught, but it is essential that the teacher ensures that the student is not just holding the information in their short-term memory, from where it will quickly evaporate, if not effectively cemented into the long-term memory. This can be achieved by techniques such as repetition, association, and mnemonic devices.

Psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus was one of the first to scientifically study forgetting. In experiments where he used himself as the subject, Ebbinghaus tested his memory using three-letter nonsense syllables. He relied on such nonsense words because relying on previously known words would have made use of his existing knowledge and associations in his memory.

His research indicated that total recall (100%) for him was achieved only at the time of acquisition. Following that, retention dropped away very quickly:

- Within 20 minutes 42% of the memorised list was lost.

- Within 24 hours 67% of what he learned had vanished.

- A month later 79% had been forgotten with a meagre 21% retention.

The conclusion is that to improve memory, we should:

- Learn to connect new information with what we already know. Use memory hooks and other mnemonic devices to represent the new information in terms of already familiar concepts.

- Activate the information in regular, spaced intervals. We profit most from a review just before forgetting, and it is also important that the recall is active. We should not just re-read the new information but reply to a question about the new information. Like that the brain will be forced to activate the memory and to deepen the neural connections.

4. Affective factors

* Why is my student Jordi terrified of speaking English and trembles while doing so while Emilio is confident even though he makes many more mistakes? What can I do to help Jordi?

Affective factors are conditions such as the attitude and emotional reactions of learners, which have an effect on the learning process and thus must be taken into consideration by the teacher. These factors can be categorized in the following groups: motivation, opportunity, environment and personality.

The level of motivation of the learner clearly has a great impact on the outcome of the learning process. We can see at school level that students who are highly motivated and apply themselves in classes and engage with their own learning process achieve much better results than those who do not. Related to motivation is the extent to which the learner feels a need to learn the material in question, a sense of necessity is the greatest motivating factor. The role of the teacher is often to inspire students to be motivated, if they are not already, often through encouraging and engaging learners with interesting material.

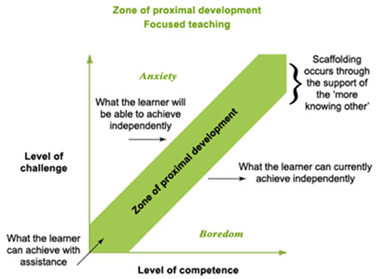

The opportunities that a learner is given to extend their knowledge of the target language are what enables them to progress and this relies on learners being exposed to sufficient L2 input. Learners should also be exposed to L2 language content that is slightly above their current level as this gives them the opportunity to expand their knowledge of the target language. However, it can’t be too difficult for them, since that might make them anxious and affective filters (negative affective factors) might come along. A way of understanding the need of controlled circumstances is referring to a concept that one of the most important contributors to Constructivism, the Russian psychologist Vygotsky, named the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The ZPD would be the distance between a student’s ability to perform the task with the help of a more skillful other and the student’s ability to do it independently. Vygotsky assured that learning took place in this zone, and its relation to affective factors can be represented by the following graph:

The learning environment is also central to second language acquisition, an environment that encourages the learner to produce language frequently and without inhibition is said to be most beneficial.

The personality of the learner is a further significant consideration, with characteristics such as introversion, low self-esteem and anxiety presenting potential obstacles to L2 acquisition. If a learner is restricted by their inhibitions in class, their progress will be lesser than a learner who is keen to communicate and open to the language learning process. The teacher must be aware of these factors, as they can sometimes act as barriers to learning and try to adapt classes, teaching styles and activities to enable each student to reach their potential.

UNIT 2: HOW PEOPLE LEARN LANGUAGES

1. First language acquisition

Language acquisition is the process by which humans acquire language skills; from the stage of understanding to the stage of producing and using it to communicate. The term first language acquisition is used to refer to the acquisition of the mother tongue, since there are cases in which other languages are learnt and used throughout life.

Researchers prefer to talk about acquiring a language rather than studying or learning it. Acquisition is a consequence of learning, but not necessarily of studying. In this sense, study and learn have different connotations. While the former suggests effort, the latter suggests ease. The term acquisition was originally used to emphasise the subconscious nature of the learning process, but in recent years learning and acquisition have become largely synonymous.

So, acquiring a language has to do with the natural ability of human beings to learn languages, and not so much with what methodologies and processes we apply to achieve it. A child living in a foreign country, for example, normally acquires the local language without studying it. Or at least he learns how to understand and then how to speak without studying, since reading and writing are abilities that are explicitly taught; normally at schools.

The analysis of how we learn or acquire a language is a relatively new discipline. It is closely related to several other disciplines; including linguistics, sociolinguistics, psychology, neuroscience and education.

Research on these fields has shed light on the fact that infants posses early mechanisms for understanding language, and that these mechanisms guide their language development.

Following this idea, it’s important to understand how psychological theories on how people learn and language development come together. The concept language acquisition as it has been described, for example, would belong to a cognitive epistemology and not to a constructivist one, since it refers to a natural ability that people have inside their brains and not to a tool people use to create their own subjective representations of what they experience.

The following conclusions on mechanisms that guide language development, on the other hand, could have a cognitive or constructivist correspondence (mentioned in the book How people learn by John D. Bransford):

- Infants distinguish linguistic information from non-linguistic stimuli (like dog barks or telephone rings) and by 4 months of age they show a preference for listening to words over other sounds.

- Young infants learn to pay attention to features of speech such as intonation and rhythm, which help them get information on meaning. As they get older, they concentrate on utterances that share a structure that characterizes their maternal language and neglect utterances that do not. Around 8-10 months of age, infants stop treating speech as mere sounds and begin to represent the linguistically relevant contrasts (e.g. “ra” and “la” can be learned by very young English and Japanese babies, but then they only retain the one that is relevant to their mother language).

- Young infants are attracted to human faces, and look especially at the lips of the person speaking, expecting some coordination between mouth movements and speech.

- Young children try to understand the meaning of language spoken around them and they start learning how to participate because of inferences about what someone must mean depending on the surrounding context. E.g. a child would bite an apple whenever asked to “eat an apple” or “throw an apple” on a high chair and she would throw it in her playpen when given the same two instructions, just assuming that she should “do what you usually do in this situation”

- But children have opportunities for learning because they use context to figure out what someone must mean by various sentence structures and words. E.g. the same child could determine the general meaning of “apple”, “eat”, and “throw”. So, language acquisition cannot take place in the absence of shared social and situational contexts because the latter provide information about the meanings of words and sentence structures and the child uses meaning as a clue to language rather than language as a clue to meaning.

The above are details on language development, but not actual theories on how a language is acquired. For a review of these you should refer to the article The Relationship between First and Second Language Learning Revisited by Vivian Cook, (Section: 2. L1 acquisition theories and L2 acquisition).

2. Second language acquisition

Second language acquisition (SLA) or second language learning is the process by which people learn a second language, and a second language (L2) refers to any language learned in addition to a person’s mother tongue.

Just as first language acquisition per se doesn’t have to do with the methodologies and processes we apply to achieve it, SLA refers to what learners do, and not to language teaching practices.

There has been much debate about exactly how language is learnt, and many issues are still unresolved, but this debate has led to a number of theories of second language acquisition. One of the most sounded theories is that of the American applied linguist Stephen Krashen, known as the Monitor Model, developed in the 1970s. Briefly explained, this model was based on five hypotheses:

- The acquisition-learning hypothesis: here is where the subconscious nature of language learning comes in, stressing that it’s extremely important that there be meaningful interaction in the second language through natural communication; speakers not being concentrated on linguistic forms (how something is said) but on what is said during a communicative act.

- The monitor hypothesis: this hypothesis states that learning influences acquisition, since the learning system performs the role of a ‘monitor’ or ‘editor’. This would mean that the only purpose of learnt language (taught and studied as grammar and vocabulary) is to check our spontaneous use of it; for the more we monitor what we’re saying the less spontaneous we are.

- The input hypothesis: this explains how language acquisition actually takes place, defining that it is bound up with the nature of the language input learners receive. According to this hypothesis, a learner progresses only when he or she is exposed to comprehensible input that is slightly beyond his or her linguistic competence. Comprehensible input, in that sense, would be target language that the learner could understand through context, explanation, rewording, visual cues, meaning negotiation, etc. but not produced.

- The natural order hypothesis: this hypothesis is based on the idea that grammatical structures follow a ‘natural order’ that is predictable, some being acquired at an earlier stage, and generally independent of learners’ age, mother tongue and conditions of exposure. In spite of this, Krashen rejects that a language program syllabus should be based on the order found in studies that support this hypothesis.

- The affective filter hypothesis: lastly, Krashen states that motivation, self-confidence and anxiety play a facilitative role in SLA. Low motivation, low self-esteem and debilitating anxiety can raise affective filters that block the use of comprehensible for acquisition. Going further, positive affect is necessary but not enough for acquisition to take place.

So, according to the acquisition-learning hypothesis, the meaning of things being communicated is more important for second language acquisition than their form, and there is a general agreement among researchers that learners must be engaged in decoding and encoding messages in L2 for the conditions to be right for second language learning. In that sense, learners must also be engaged in creating pragmatic meaning (meaning which depends on the context) in order to develop fluency.

On the other hand, according to the monitor hypothesis, some sort of focus on form does appear to be necessary for SLA. Some advanced language structures may not be fully acquired without the opportunity for repeated practice. Schmidt’s Noticing hypothesis states that conscious attention to specific language forms is necessary for a learner’s interlanguage to develop. This attention does not have to be in the form of conscious grammar rules, however; the attention is on how each specific form affects the meaning of what is being said. To put it in simple words, it is absolutely necessary to explain the correct form if a confusion in the message occurs by using the wrong form, or a student conveys the wrong message.

Interlanguage

* Emilio speaks Spanglish, is that a language?

If you remember back in the Language Analysis Module, a language was defined as a system of communication, and for there to be communication everyone involved has to have some shared knowledge of that communication system. That knowledge might be incomplete, but that doesn’t mean that the person can’t communicate the message. When the message is conveyed inaccurately then we say they’re using an interlanguage. Interlanguage is the language used by a learner who is not yet proficient in L2 usage, and it’s somehow always present until the person becomes fully bilingual, since learners tend to be constantly influenced by the structure of their mother tongue.

There are three different processes that influence the creation of interlanguage:

Language transfer. Learners fall back on their mother tongue to help create their language system. From this interlanguage perspective, this is not recognized as an error, but as a process that all learners go through.

Overgeneralization. Learners use rules from the second language in a way that native speakers would not. For example, a learner may say “I goed home”, overgeneralizing the English rule of adding -ed to create past tense verb forms.

Simplification. Learners use a highly simplified form of language, similar to speech by children or in pidgin. This may be related to linguistic universals.

As mentioned in the natural order hypothesis, in the 1970s there were several studies that investigated the order in which learners acquired different grammatical structures that showed that there was little change in this order among learners with different first languages. Furthermore, it showed that the order was the same for adults as well as for children, and that it did not even change if the learner had language lessons. This proved that there were factors other than language transfer involved in learning second languages, and thus a strong confirmation of the concept of interlanguage.

However, the studies did not find that the orders were exactly the same. Although there were remarkable similarities in the order in which all learners learned second language grammar, there were still some differences among individuals and among learners with different first languages. It is also difficult to tell when exactly a grammatical structure has been learned, as learners may use structures correctly in some situations but not in others. Thus it is more accurate to speak of sequences of acquisition, where particular grammatical features in a language have a fixed sequence of development, but the overall order of acquisition is less rigid.

Differences between L1 and L2 acquisition

* Is it children or adults that learn a second language faster?

Here’s a summary of the ideas Vivian Cook’s paper The Relationship between First and Second Language Learning Revisited says on the matter:

Some of the differences between first languageand L2 acquisition are intrinsic and cannot be avoided and others are accidental in that they vary according to the circumstances in which acquisition takes place (e.g. inside or outside a classroom). In the vast majority of cases L2 learners are older than L1 children, and age inevitably brings with it a host of factors that have little to do with language acquisition itself. The discussion here excludes early childhood simultaneous bilingualism, considering this as a separate process in which first and second languages are not consecutive.

Factor 1: The lack or presence of another language in the mind

L2 learners already have at least one other language in their minds, so the initial language state of their minds is in principle different from the L1 child because of the first language knowledge. This coexistence of two languages in the same mind, leads to the vast area of transfer: L1 to L2, L2 to L1 (reverse transfer) or one L2 to another L2 (lateral transfer). In that sense, L2 acquisition necessarily differs from L1 acquisition because everything the learner acquires and does potentially involves both first and second languages.

* How come Emilio sometimes uses French numbers while counting in English but he never really confuses English with Spanish, which is his native tongue?

Weinreich (in his book Languages in contact, 1953) suggested that two of the forms bilingualism may take are coordinate bilingualism in which the languages are effectively kept in separate compartments and compound bilingualism inwhich they are in contact. However, there might be an integrative continuum, which sees a continuum from total separation to total integration of the two languages rather than discrete compartments. In this case, the point on the continuum would vary for individual L2 learners, for different aspects of language and for different situations. That is to say, the L1/L2 mental relationship has many variations and cannot be stated in simple terms even for a particular individual, whose L1 and L2 vocabulary say may be closely linked, but whose L1 and L2 phonologies may be quite distinct.

Factor 2: The comparative maturity of the L2 learner

L1 acquisition has seen continual controversy over the links between language development and social and cognitive development. At one extreme Universal Grammar theorists (theory normally credited to Noam Chomsky) attempt to isolate language from other cognitive systems. To them the controversy concerns maturity of the language faculty itself, whether it is essentially the same from birth, just requiring language experience or exposure or whether the faculty itself matures. At the opposite extreme, language development has been directly tied to cognitive development (e.g. the child’s development of vocabulary goes along with the expansion in the child’s short-term phonological memory) and social development (e.g. children slowly develop the ability to talk to their peers and they have no idea of when to whisper).

L2 learners start from the position of having done all of this once already. They are older and more mature than the L1 child and so have whatever advantages that age confers in terms of working memory, conceptual and social development, command of speech styles, and so on. Once a child has learnt how to mean, they are no longer the same person and cannot regress to a point where they no longer know how to mean: language itself is there for the L2 learner, even if the specific second language is not.

Another major factor in many L2 learners’ lives is literacy. Learning to read and write changes people’s thinking and brain structures (e.g. Japanese children remember geometrical patterns better than English children because their writing system is more visually than phonologically based and English readers place images of events such as breakfast, going to school, going to bed etc in a left-to-right order, while Hebrew and Arabic readers use right-to-left order).

Age has often been blamed for alleged deficiencies in L2 acquisition. However, it is not age per se that shuts the door but maturation on a particular scale: it’s not being 30 that prevents you from learning a new language but having the memory system, the cognitive abilities and the social situations etc of a 30-year-old. The variable is not age itself, but the inevitable companions of age.

Factor 3: differences in situation, learner and language input

The vast majority of children acquire their first language in a primal family care-taking situation. L2 learners, however, encounter the second language in a variety of situations. One overall group of L2 situations can be called natural, i.e. picking the language up through encounters at work etc., and another group are artificial, i.e. learning it through instruction of one kind or another. In either case, the people the learners speak to are not necessarily making concessions to their lower language knowledge, and are certainly not in charge of their lives in the way that an adult is in charge of a child. Teaching practices vary round the world far more than child-rearing practices and they change rapidly according to the changing winds of language teaching. Neither the natural nor the artificial L2 situations come in a standard package, as L1 situations usually do.

Also, children barely differ in their acquisition of the first language; meaning that they all end up learning the phonology, vocabulary and grammar appropriate for their dialect, class, age, gender, etc. Individual differences in second language acquisition, however, are extreme. You can’t learn a second language, apparently, without having the right motivation, attitude, learning style, learning strategies, cognitive style, personality and many other factors; mostly concerned with artificial classroom learning. The majority of L2 students give up before they pass the threshold when the L2 becomes genuinely useful to them; allegedly 80% of all students of English in the world are beginners, implying only a small proportion go on to higher levels. Apparently, success in L2 learning is a matter of individual variation and success in L1 acquisition is not.

The language input in L1 also differs dramatically from that provided to the L2 learner (although in natural contact situations the input is closest to that in L1 acquisition). Native speakers speaking to non-natives simplify their speech in ways known as foreigner talk but hardly simplify topics in the same way parents do to children. On the other hand, in the artificial teaching situation, course books and language teachers simplify the language in various ways. The Interaction Hypothesis has however maintained, since 1981, that what is necessary is simplified interaction, not simplified language, undeterred by the lack of proof for its necessity in L1 acquisition.

Factor 4: the alleged lack of success of L2 acquisition and its causes

* Why does my neighbour’s 4-year-old girl, who has a Spanish mother and British father and was born in Spain, speak fluently both languages? And how can I help Montserrat, my 55-year-old student, to achieve a native like level of English? Will she ever make it?

According to many, the crucial difference between first and second language acquisition is the success of L1 acquisition versus the failure of L2 acquisition, since there’s a lack of general guaranteed success in adult foreign language learning. Normal children inevitably achieve perfect mastery of the language, but adult foreign language learners do not.

The task of SLA research is then taken to explain why adults fail to achieve full native-speaker competence. If an L1 child can master a language in a few years, why can an L2 learner not do the same over many years?

The explanations for this lack of success have drawn on many of the ideas presented earlier and some are to do with the transformative power of maturation: L2 learners are intrinsically not the same people as young monolingual children.

- Universal Grammar may not be available in second language acquisition

- the greater capacity adult short-term memory system may be a handicap

- adults rely more on explicit learning

- declarative memory declines physically

- adults are in the formal operational stage of development, which is a handicap to language acquisition

Other explanations put the lack of success down to features of the environment

- the concentration on the here and now in conversations with children is lost in adult conversation

- Adults are more likely to be learning in formal classrooms that are less conducive for natural acquisition

In any case, the issue of success is a red herring. The child is learning their first language and has no other: the L2 learner is learning a second language when they already have a first. L2 learners are only failures if they are measured against something they are not and never can be – monolingual native speakers. The success of L2 users is not necessarily the same as that of monolingual native speakers; they are doing different things with language with different people and have a range of other abilities for code-switching and translation no monolingual native speaker can match.

If you expect L2 knowledge and processing to be identical to that of a monolingual speaker of the language, you’re going to be disappointed. Whatever the differences between L2 learners and L1 children, they are not a matter of success but of difference. The rationale for comparing them with the monolingual native speaker is convenience; since L1 acquisition research has a range of discoveries and techniques that SLA research can draw on. But, unless used carefully, they only measure L1 success, not L2 success.

Individual variations in SLA

* What is the best age to start learning a second language?

It was thought years ago that the earlier you start learning L2, the better, but modern theories reject very early guided learning. They insist more on the approach rather than the early age factor.The issue of age was first addressed with the critical period hypothesis. The strict version of this hypothesis states that there is a cut-off age at about 12 years old, after which learners lose the ability to fully learn a language. But this strict version has since been rejected for L2 acquisition, since some adult learners have been observed to reach native-like levels of pronunciation and general fluency.

Of course for children it is more natural as they don’t question grammar rules, don’t try to apply the structure of their own language to L2, are not so tempted to try to translate literally, and, in general, their flexibility and lack of fear of speaking make them excellent learners; but that doesn’t mean that adults can’t be an excellent learners also. Rather than be concerned about the age of the learner, we have to ask: what the motivation of the learner is, the exposure to English that they have, their reasons for learning the language, and, above all, what approach they take to do it.

* But, how long does it take to learn a language?

Many students will ask you this question and many school will make easy promises for fast learning but we always answer this question with another one: How long is a piece of string? There are many factors that affect this including: motivation, exposure to the language, the need of the student and the approach or methodology. Unfortunately there is no short cut or easy promise. Perseverance, exposure (input and output) and approach are key elements in this equation, but there are others, which also have to do with individual variations.

* Why do people, in general, learn at a different pace?

It has been mentioned before that adult learners of a second language rarely achieve the native-like fluency that children display. But they also often progress faster than them in the initial stages. This has led to speculation that age is indirectly related to other, more central factors that affect language learning. Recent research has focused particularly on:

- social and societal influences

- personality traits (e.g. extroverts are better language learners than introverts)

- motivation

- learner’s attitude to the learning process; affective factors (e.g. anxiety in language-learning situations has been almost unanimously shown to be detrimental to successful learning)

- strategy use

Actually, there has been considerable attention paid to the strategies which learners use when learning a second language. They have been found to be of critical importance, up to the point that strategic competence has been suggested as a major component of communicative competence. Strategies are commonly divided into learning strategies and communicative strategies, although there are other ways of categorizing them. Learning strategies are techniques used to improve learning, such as mnemonics or using a dictionary. Communicative strategies are strategies a learner uses to convey meaning even when she or he doesn’t have access to the correct form, such as using pro-forms or generic words like ‘thing, this, here, to get, something’, or using non-verbal means such as gestures.

Early stage (S1) learners’ material at Oxbridge has been designed to develop powerful communicative strategies with little linguistic resources. The usage of generic words or pro-forms is constantly reinforced as they are carriers of an enormous communicative potential.If a learner uses generic words or pro-forms such as thing, this, here, to get, something, etc. it is very easy to substitute them with the concrete objects or actions they refer to: e.g. In the sentence “I want this”, “this” can be substituted by “an apple” and becomes “I want an apple”. Even if learners do not know the names of concrete objects, by knowing generic words they can make their point in communication.

And regarding general conditions, let’s not forget that we like the subject because we like the teacher and that affection is very important in the learning process at any age. Both children and adults learn more if they create good rapport with their teacher.

3. Language processing

* What exactly does it mean to go step-by-step, little by little and one thing at a time?

The way learners process sentences in their second language is also important for language acquisition. According to MacWhinney’s Competition Model, learners can only concentrate on so many things at a time, and so they must filter out some aspects of language when they listen to a second language. Learning a language is seen as finding the right weighting for each of the different factors that learners can process.

Similarly, according to processability theory, the sequence of acquisition can be explained by learners getting better at processing sentences in the second language. As learners increase their mental capacity to process sentences, mental resources are freed up. Learners can use these newly freed-up resources to concentrate on more advanced features of the input they receive. One such feature is the movement of words (inversion). For example, in English, questions are formed by moving the auxiliary verb or the question word to the start of the sentence (John is nice becomes Is John nice?) This kind of movement is too brain-intensive for beginners to process; learners must automatize their processing of static language structures before they can process movement.

On the other hand, studies based on the Competition Model have shown that learning of language forms relies on the accurate recording of many exposures to words and patterns in different contexts. If a pattern is reliably present in adult language input, children acquire it quickly, and rare and unreliable language patterns are learned late and are relatively weaker, even in adults. So, reinforcing the use of such a structure like inversion at an early learning stage, can help students to automatize them before the actual acquiring of the structure occurs.

This happens for example in Oxbridge’s QQs. Beginner students struggle at first and want to know the meaning of every single example. What they learn though is something much more complex and important than it appears: they learn a fundamental construction in English very different from their mother tongue syntax schemes.

4. Learning in a natural contexts versus learning in a classroom

* Why does Sara, who went for six months to London, speak better English than Emilio, who studied it for six years at school? and what can I do to speed up Emilio’s learning process?!

While the majority of SLA research has been devoted to language learning in a natural setting, there have also been efforts made to investigate second language acquisition in the classroom. This kind of research has a significant overlap with language education, but it is always empirical, based on data and statistics, and it is mainly concerned with the effect that instruction has on the learner, rather than what the teacher does.

The research has been wide-ranging. There have been attempts made to systematically measure the effectiveness of language teaching practices for every level of language, from phonetics to pragmatics, and for almost every current teaching methodology. This research has indicated that many traditional language-teaching techniques are extremely inefficient. It is generally agreed that pedagogy restricted to teaching grammar rules and vocabulary lists does not give students the ability to use the L2 with accuracy and fluency. Rather, to become proficient in the second language, the learner must be given opportunities to use it for communicative purposes.