Warning: include(C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php' for inclusion (include_path='.;.\includes;.\pear') in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

MEANING, CONTEXT AND SOUND

UNIT 5: MEANING, CONTEXT AND SOUND

Semantics, Pragmatics, Lexicology and Phonology

1. Semantics: semantic fields

Vocabulary, or words grouped together by meaning are known to belong to the same semantic field. The amount of semantic fields are more or less unlimited. Any theme that contains a long set of words relating to it can be known as a semantic field.

e.g.

Semantic field: Transport -Car, van, metro, train, tram, etc.

Semantic Field: Computers -Mouse, keyboard, laptop, hard-wear, software, etc.

Semantic field: Professions -Nurse, teacher, truck driver, receptionist, etc.

Organising vocabulary by semantic fields is essential in second language teaching, at all levels, but especially for beginners. By teaching vocabulary in clear groups you make it easier for your students to memorise and learn new words. It also allows them to build on prior knowledge and construct more complete sentences.

Let’s imagine you have a beginner student. You have already taught them family (mother, father, cousin, husband, wife, etc.) now you are teaching professions (nurse, teacher, receptionist, etc). Knowing these two semantic fields as well as a simple grammar function, students are able to construct several different sentences.

e.g.

My father is a doctor.

My mother isn’t a teacher, she is a nurse.

I have two cousins. One is an accountant, one is a student.

2. Semantics and pragmatics: register of the language

Levels of formality

Imagine you are working in a bar. Someone comes in and shouts ‘Give me a bottle of beer!’ What would you do? You’d probably want to empty the contents of said bottle on the customer’s head, on account of their rudeness, but then you’d remember that you need the money and you’d probably think better of it. If the next customer came in and asked ‘Can I have a beer, please?’ you’d probably serve them with a smile, and maybe even give them a small portion of mixed nuts, out of goodwill.

In Spain, on the other hand, this degree of formality or politeness is not as important as in the UK or elsewhere. It is perfectly acceptable to tell the bartender ‘una cerveza!’, which would simply translate as: ‘a beer!’

Language is directly related to culture, and in most English speaking countries we are very concerned with politeness and formality. The different levels of formality in which we speak or write to different people are known as register.

We have three different types of register.

Informal (slang/colloquialism) – Think of the way you might talk to your friends and family.

Neutral – The way you would maybe talk to a stranger, ordering a drink at the bar, or maybe with an older family relative. Polite, but not over-the-top.

Formal – The type of language that you’d use at an important business meeting, maybe delivering an important speech, or if you ever got to meet the Queen! Supposing you were calling a customer service hot-line, you would expect to be treated in formal English. Normally, written English is more formal.

Ways of expressing formality

Formal language is characterised by more eloquent vocabulary and change in sentence structure (e.g. inversion and passive voice). However, even basic sentences can convey formality or a lack of.

Let’s look at the following examples, all expressing the same function.

You fancy a coffee? Do you want a coffee? (Informal)

Would you like a coffee? (Neutral)

Could I offer you some coffee? (Formal)

Close that window.

Can you close that window?

Could you close the window?

I’m going to the toilet, that OK?

Can I go to the toilet?

May I go to the toilet?

What we can see from these examples is that the use of modal verbs change the register of the sentence. When we use informal language, we rarely use any modal verbs. For neutral English we tend to use will and might. Finally, for formal English we often use may, could, would and shall.

3. Lexicology

Word formation and word families

Morphology is the branch of lexicology that studies word formation, which is the creation of words by adding prefixes and suffixes. These are parts of words that are added to the start or end of existing nouns, verbs or adjectives to make new words.

Most prefixes and suffixes are bound morphemes (since they can’t stand alone as a part of a word: un-, -ness, dis-, -ly, etc.), but not always. For example:

Unfriendly. UN = bound morpheme, friend = free morpheme, LY = bound morpheme

Comforting. Comfort = free morpheme, ING = bound morpheme

Respectable. Respect = free morpheme, ABLE = free morpheme

Prefixes are morphemes added before the word root and change the meaning of the original word.

E.g. the adjective large can become a verb by adding the prefix en- as in enlarge.

Suffixes are generally tied to a particular word class: for example, words ending in-tion are almost always nouns. However a word formed with one suffix may itself provide the root word to which another suffix is added; e.g. the noun addition may be combined with the suffix-al o form the adjective additional, which may in turn be combined with the suffix -ly to form the adverb additionally. It is the last suffix that indicates the word’s class.

Word families are groups of words that are sufficiently closely related to each other to form a ‘family’. Word families use prefixes and suffixes to form adjectives, nouns, adverbs and verbs belonging to the same family. Some examples are shown in the table below.

Noun |

Verb |

Adjective |

Adverb |

| argument | argue | argumentative | argumentatively |

| anger | anger | angry | angrily |

| suggestion | suggest | suggestive | suggestively |

| calm | calm | calm | calmly |

| word wording word-list |

word | wordy | —- |

| family familiarity |

familiarize | familiar unfamiliar |

familiarly |

Each of these families is bounded by a common root word.

Why are word families important?

Form-based families are important because they reveal sometimes hidden patterns of spelling that the students can remember and link.

An understanding of word families also allows either the form or the meaning of unfamiliar words to be guessed with some confidence. As well as this, in most western languages, prefixes, suffixes and word families follow the same patterns; helping students to identify particular rules between their native language and the language they are learning.

Phrasal verbs

A phrasal verb is a verb plus a preposition or adverb that creates a meaning different from the original verb.

EG

I really want to be a teacher, but I’m put off by all the grammar.

Often, the same phrasal verb has different meanings. Compare the above example with the next:

Due to the terrible weather, the match has been put off until tomorrow.

In the first example, put off means to be discouraged whereas the second example it means to postpone. Look at the following sentences:

I will pick up my sister at 12.30 to go to lunch.

OK, we’ve had a long break, let’s pick up where we left off.

Let’s add up the cost of the trip and split the bill.

I’ve examined all the evidence and something still doesn’t add up.

How are you getting on with the report I asked you to do?

I’m so happy you and Dave got on so well.

There are very many phrasal verbs, several of which have multiple meanings. As a result, they can be a bit of a headache for English learners. Most phrasal verbs have synonymous verb, and most students tend to use the verb rather than the phrasal verb.

I will pick up my sister = I will collect my sister.

Let’s add up the cost = Let’s calculate the cost.

Sometimes avoiding the use of phrasal verbs can sound a bit strange to a native speaker. This is why studying phrasal verbs is very important.

While we normally teach phrasal verbs to higher levels, some very common and simple phrasal verbs are introduced at an early stage. EG

Stand up

Sit down.

Wake up.

Get up.

Fall down.

Idioms

It’s after the Christmas holidays and you are informing your students that the festive season has cost you an arm and a leg. You gleefully observe their confusion as they count each of your limbs making sure they are all made of human flesh and bones. You then proceed to tell them that while you had a great time it was raining cats and dogs almost every day. You can’t hold back your laugh as your student replies ‘but in Spain it rains water…’

Obviously, in your country as well as your students country, you buy things with money not body parts, and it rains water too. These little figurative expressions are known as idioms and in English, as with most languages, there are hundreds.

For students, idioms are difficult to learn and they are less important than phrasal verbs. Occasionally they are fun to do with higher level students and if they are taught well, the students find them interesting.

When teaching idioms, don’t teach too many. Four to six is a good amount. Also idioms should be taught within a similar context:

Idioms to do with love/ relationships: to have a crush on someone, head over heels in love, love at first sight, made for each other.

Idioms to do with money: To be skint, bring home the bacon, to be broke, make a fast buck, to be loaded.

English really is a piece of cake!

Proverbs

Proverbs are similar to idioms, but they offer some sort of guidance or advice:

An apple a day keeps the doctor away.

Absence makes the heart grow fonder.

Rome wasn’t built in a day.

4. Phonology

Pronunciation

Teachers usually need to correct grammar errors and rectify many different mistakes. With experience, teachers learn to find a balance between correcting and allowing students to gain confidence and fluidity. However, teaching good pronunciation can often be difficult and it is something that many students struggle with. If you were to speak to a non-native speaker it would normally be easy to figure out where they are from. Their accent and pronunciation would be a giveaway.

It is important at this stage to make a distinction between accent and pronunciation. Your accent is your way of pronouncing a language. You have formed your accent due to family, friends and the area that you have grown up in. There are hundreds, if not thousands of accents in English. It would be unfair to expect your students to form a perfect English/American/Irish/Scottish accent. And in any case; which accent is a correct English accent? Is it London? Yorkshire? Manchester?

We can’t expect our students to speak perfect BBC English but we can strive to make their pronunciation as neutral as possible.

In order to do this we must pay attention to individual sounds, connected speech, individual sounds, word stress and intonation.

Individual sounds

A phoneme is an individual sound; each language has its own set of them.

English has 44 (not to be confused with letters).

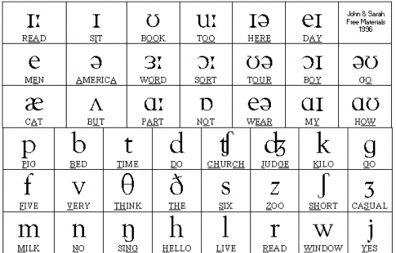

Below is the chart of the phonemic symbols used in English to classify English sounds. If you open any dictionary, you can see that after every word in brackets there is a phonetic transcription of how the word is pronounced. The symbols below are internationally used to describe the pronunciation of words in any language:

Connected speech

When we speak naturally we do not pronounce a word, stop, then say the next word in the sentence. We. Do. Not. Speak. Like. Robots. To make speech flow smoothly, we pronounce the end and beginning of some words differently depending on the sounds at the beginning and end of those words.

These changes are described as connected speech.

Word stress

In words of two or more syllables, one syllable is spoken with more emphasis, i.e. it’s longer than the other(s).

In English we do not give every syllable equal emphasis, which means some are stressed. We always give one syllable extra emphasis and the others are said quietly. Examine the following sentence:

The band are going to record their first record.

“Record” is spelled the same in both words but they have different meanings. How do you know? Word stress! There are a host of words in English which are spelled exactly the same but one is a noun and the other is a verb.

As a general rule most 2-syllable nouns have the emphasis on the first syllable. RECord, PRODuce, PREsent…

Most 2-syllable verbs have the emphasis on the second syllable. recORD, prodUCE presENT…

Sentence stress

In utterances longer than a single word, key words which carry the main information are emphasized and the others are not.

Sentence stress is the real rhythm of English. We dance over some words and linger on others, but which words and why do we do it? Most sentences have two different types of words, structure words and content words.

Content words are the key words of the sentence. They are the words which carry the meaning of the sentence.

Structure words are less important words. They fill out the sentence and make it grammatically correct, but are not essential to conveying the meaning of the sentence. You can remove the structure words and still convey the meaning of the sentence, but you cannot remove the content words.

Take these words for example: COMING TOMORROW SPEAK SOON. This sentence is not complete or grammatically correct but you can take a good guess at the meaning.

We can add some more words to fill out the sentence but the meaning is still the same:

I’m COMING home TOMORROW SPEAK SOON.

We can then make a complete sentence:

I’m COMING (home) TOMORROW (so we can) SPEAK SOON

1syllable 3 syllables

But as you can see, the meaning has not changed. If you look at the sentence carefully and say it in your head, you’ll see that there is definite emphasis on each of the content words. Also you’ll notice that between COMING and TOMORROW we have one syllable, and between TOMORROW and SPEAK we have three syllables. However, as speakers we jump over the three syllables quicker and say them in effectively the same time as one syllable. So as native speakers what we do (without realizing) is say the structure words quicker or slower to maintain a ‘beat’ with the content words. This is the rhythm of English!

We also tend to use stress for emphasis.

I told HIM to finish the report. (HIM not her or the other person)

I told him to finish the REPORT. (He was to finish the report, not the presentation.)

I told him to FINISH the report. (He obviously hasn’t finished the report.)

The same sentence can have a slightly different meaning or connotation, depending on which word is emphasized.

Intonation

Intonation is the pattern of rise and fall in the pitch of the voice; it often adds meaning to the message, e.g. surprise, question, request, command.

The rising and falling of the voice is called intonation. It is the music of language.

Intonation patterns are different in different languages. L2 speaker usually transfer the intonation of their own language over the intonation of L2.

Usually we use falling intonation at the end of a sentence to indicate a pause.

We use rising intonation in questions.

Still, there may be some cases when the intonation adds different meaning to the sentence.

Let’s see the example:

You don’t like going to the cinema, do you?

A falling intonation at the end of the tag question would indicate that you ask for confirmation about something you already know.

A rising intonation at the end of the tag question would indicate that you are unsure and don’t know the exact answer.

5. Semantics, pragmatics and phonology: Homonyms, homophones and homographs

For the purposes of English teaching and learning, we need to know these three phenomena and make our students aware of them.

Homonyms – two (or more) words are spelt the same but have different meaning.

Eg.

bat (animal) – bat (object), bow, bank, bear, lean, lap, type

Homophones – two words sound the same but have different spelling.

Phase – face

Mail – male

Plain – plane

One – won

Read – red

Bored – board

Homographs – two words with the same spelling and different meaning and pronunciation.

E.g.

read / read

live / live

minute / minute

lead / lead