Warning: include(C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php' for inclusion (include_path='.;.\includes;.\pear') in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

SENTENCE STRUCTURE AND PUNCTUATION

UNIT 4: SENTENCE STRUCTURE AND PUNCTUATION

Structure of the English sentence

Syntax is the branch of linguistic study that deals with the order and functions of the words in a sentence.

Why is it important to analyse?

The order of words in a sentence can vary from language to language, and so do the linking constructions, therefore it is important to know and understand the rules of English syntax in order to teach it properly.

When it comes to parts of speech conforming sentences, we should consider that the same part of speech could adopt different behaviours according to its function in a sentence. Thus, a noun in a sentence can be the subject (or performer) of the verb action, but it can also be the receiver (or object) of the verb action. In some languages, the different functions of the words are expressed by different terminations or inflexions; as in Russian, German, Croatian, and others. In English these differences don’t affect the word form. Instead, we use prepositions to show the relationships between elements.

1. What is a sentence

According to Bloomfield a sentence is ‘an independent linguistic form, not included by virtue of any grammatical construction in any larger linguistic form’.

Technical definitions aside; a sentence can be seen as a string of ‘units’ or blocks of language in a certain order. These units consist of words or phrases, and to change the meaning we change the words or phrases, but the order remains the same.

E.g.

I like snails.

We all work very hard.

People need people.

In written language we recognise sentences because they begin with a capital letter and finish with a full stop at the end. However, in speaking it isn’t very clear where one sentence starts and another finishes.

Clauses, on the other hand, can be clearly identified in both speaking and writing, since each clause conveys a full idea. For example, the sentence ‘I’ll keep my fingers crossed because I believe it’ll help you’ is clearly made up of two complete ideas, and thus two clauses: ‘I’ll keep my fingers crossed’ and ‘I believe it’ll help you’.

2. Sentence parts

So, sentences are made up of clauses, and clauses can be divided into further ‘constituents’, each of which may consist of one or several words. Depending on whether we look at constituents from the perspective of what they are or what they do we choose different terms. For example, a sentence might be made up of noun phrases, verb phrases, preposition phrases, adjective phrases, and/or adverb phrases. However, a noun phrase might be a subject, object, complement or adverbial depending on its function and position in a sentence.

In general, there are two basic parts in which a sentence is divided: subject and predicate.

Subject

Subjects usually come before the verb phrase in a clause, and frequently consist of a noun phrase, although many other clauses or forms of verbs might apply. These are examples:

| Subject | Predicate |

| The student I told you about yesterday | sent me an email. |

| To lose | is difficult. |

| Drinking | can kill. |

| How to make money | always sells. |

| Whether or not you said that | is irrelevant. |

Sometimes students define the subject as ‘the performer or doer of the action or state expressed by the verb’, but the above examples show that a subject is a much broader category than that. Also, if you think about passive constructions e.g. ‘The award was granted to him’, then by no means is the subject the performer of the action.

The subject actually identifies what or who is the topic of the clause and/or the agent of the verb. Almost always we need a subject to form a meaningful idea. As grammarians understood the importance of this element for a complete sentence, they called it a subject.

And because it is so important, in affirmative statements, it goes at the beginning of the sentence. We practically always start by announcing the subject before anything else in a sentence: John drinks coffee; Mary plays tennis; They behave as children. Consider, however that they are some exception: Well, maybe a little bit of lemon would be nice; There goes the expert.

There are also other cases in which the subject is omitted, as in the imperative form. The sentence ‘Follow my instructions’ is a complete and meaningful one, but has no subject before the verb.

In an interrogative sentence, the word order of the subject and the verb is inverted, that is, that verb precedes the subject. E.g. Is John a teacher?

Subjects can be nouns (Dogs are loyal.), pronouns (We study together) and noun phrases (Me and my friends are going to the cinema tonight), but also verbs (Studying is important nowadays) and verb phrases (Knowing the exact answer will help you in an interview).

Predicate

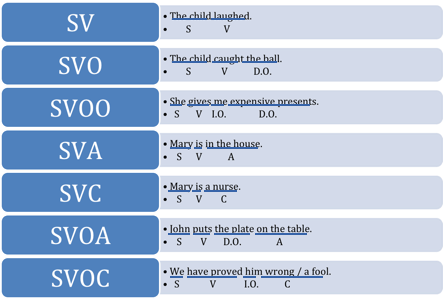

The predicate is everything else that’s not a subject, including the verb phrase of the sentence. We could say that there are five different types of predicate (or clauses), that result from the combinations of the types of constituents that might come up. The following table shows these five types of predicate (and clause) and the order in which constituents occur:

Subject |

Predicate |

|||

| Verb phrase | Indirect object | Direct object | Complement | |

| She | likes | |||

| She | has been | bad-tempered. | ||

| She | gave | her brother | the keys. | |

| She | calls | her husband | ‘honey’. | |

| She | ||||

Aside from these four types of constituent: verb or verb phrase, indirect object, direct object, and complement; sentences might also contain an adverbial. E.g. She gave her brother the keys this morning.

Now let’s look at these constituents independently:

Verb or verb phrase (V)

The verb expresses the main action or state of the sentence. It carries an enormous importance and constitutes the main axes of the sentence. Actually, the constituents that follow (if any) are determined by the verb we choose.

In a sentence, verbs fall into two types: transitive or intransitive verbs. A transitive verb is incomplete without a direct object, meaning that the verb needs something to complete it.

- The bottle holds. (What? This sentence is incomplete without an object.)

- The bottle holds water. (Water is the direct object, necessary for the complete sense of the sentence, thus making hold a transitive verb.)

- The committee named. (What? Incomplete sentence)

- The committee named a new member (again, a new member completes the information offered by the verb)

- The child broke (What? Information missing)

- The child broke the plate. (Now it makes sense.)

An intransitive verb, on the other hand, cannot take or doesn’t need a direct object.

- The plant has thrived in the garden. (‘in the garden’ is not absolutely necessary for the sentence, it only adds information)

- The train arrived 4 hours late. (‘4 hours late’ is the additional or optional part in this sentence)

You can put a full stop after ‘thrived’ and ‘arrived’, and the sentences still retain their meaning.

Object (O)

The object of a sentence is the receiver of the action or the state expressed by the verb. It indicates what has been transferred from the subject through the verb.

Objects are mainly direct and indirect, but there’s also a third type called prepositional.

The direct object receives the action of a transitive verb. We’ll find it if we ask the question “What?”

The children caught the ball.

S V D.O.

The indirect object is the indirect receiver of the action expressed by the verb. It indicates ‘to who’ or ‘for who’ is the action related to. We’ll find it if we ask the questions “Who?” or “To whom?”

We gave the present to my mom.

S V D.O. I.O.

The prepositional object follows a verb that requires a fixed preposition. These are verbs such as laughed at, look at, look forward to, look after, think of, consist of, depend on and many, many others.

His classmates laughed at him.

S V Prep.O.

Complement (C)

A complement is the part of the sentence that gives you more information about the subject or object (e.g. what it is, how it feels, or what it is like) and it is necessary for the complete meaning of the sentence. They usually follow the verb ‘to be’ or, in general linking verbs, which are synonyms of ‘to be’: e.g. seem, appear, become, fell. For example:

Mary became a nurse. (nurse is a noun)

Mary is a nurse.

Mary seems nice. (nice is an adjective)

Mary is nice.

Nurse and nice are complements, as they can’t be removed from the sentence whilst retaining meaning. But the verb phrase being a linking verb is not enough for whatever comes next to be a complement. For example, in the sentence ‘Mary is in the house’ in the house is not a complement, since it says where Mary is, but doesn’t give more information about her being. In this case in the house is an adverbial or adjunct.

Adverbial or Adjunct (A)

The adverbial, also known as adjunct shows the time, place, purpose, result, manner, condition of the action expressed by the verb (When, Where, Why, How…)

-John puts the plates on the table. (adverbial of place)

-Every day we go to the swimming pool. (every day = adverbial of time; the swimming pool = adverbial of place)

-He gets up at nine o’clock in the morning. (adverbial of time)

- She touched the flowers gently. (adverbial of manner)

English syntax (almost) always follows the rules SVO (subject-verb-object) or SVA (subject-verb-adverbial) in affirmative statements. We will study these, as well as a few exceptions.

If we take a simple example such as ‘A guy came to the bar’ we can see that it follows the rule SVA. It is incorrect to say ‘to the bar came a guy’ or ‘came to the bar a guy’, as this puts the verb before the subject. It should be noted that in other languages a syntactical order like this is allowed, therefore it is important to understand that some learners will tend to transfer their own rules to the target language.

3. Types of sentences

The sentences we’ve used as examples up until now belong to the category ‘statements’, but there are other types of sentences.

Functions of sentences

According to their function sentence fall into four categories:

1. Statements (affirmative or negative)

o John is brave. (affirmative)

o John isn’t brave. (negative)

2. Questions (interrogative)

o Is John brave?

3. Exclamations (exclamatory)

o What a brave man is John!

4. Commands (imperative)

o John, be brave!

Structural complexity of sentences

According to their structural complexity sentences can be simple, compound or complex.

Simple

Simple sentences have one clause, which means they have only one verb. They are made up of two parts: Subject and predicate (verb + complements or objects + adverbials).

The children caught the ball.

S V D.O.

Mary is a nurse.

S V C.

You can write forever using simple sentences, but it would sound immature and it is not pleasant to read:

James went out. He spoke to Marta. They had a drink. There was music. They had a great time.

Compound

A compound sentence contains two or more independent clauses, joined by a conjunction, like ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘or’.

Simple: James went to London. He bumped into Marta.

Compound: James went to London and bumped into Marta.

Notice the two clauses are independent; they can stand alone as simple sentences and the reader cannot tell which is more important. This is the crucial difference between a compound and a complex sentence.

Complex

Complex sentences are made up of two or more clauses, at least one of them being a dependent clause.

Simple: James went to London. He bumped into Marta.

Complex: Since James went to London, he bumped into Marta.

Notice how ‘Since James went to London’ is now a dependent clause, i.e. it is incomplete and cannot stand on its own as a sentence or clause. When you write the subordinating conjunction ‘since’ at the beginning of the first clause, however, you make it clear that ‘going to London’ is less important than, or subordinate, to ‘bumping into Marta’.

Linking constructions by conjunctions

In order to link ideas together we use linking conjunctions. As in speech, clauses link together by means of conjunctions to form more complex ideas into one grammatical unit. Let’s see in what ways this is done.

There are two main ways of putting clauses together:

- Co-ordination, by which a compound sentence is formed.

- Subordination, by which a complex sentence is formed.

And three main types of conjunctions:

- Coordinate, which are only: and, but, for/as/because, nor, or, so, and yet..

- Correlative, which work in pairs to join words or groups of words of equal weight in a sentence, there being 6 pairs: either…or, neither… nor, both… and, whether… or, not only… but (also), and just as… so.

- Subordinating, which can be further analysed according to their form:

3.1. Simple subordinating conjunctions: after, (al)though, as, because, if, like, once, since, that, till, unless, until, when(ever), whereas, whereby, whereupon, while, whilst, etc.

3.2. Compound subordinating conjunctions: in that, so that, in order that, such that, except that, for all that, as far as, as long as, as soon as, so far as, rather than, as if , as though, in case, etc.

3.3. Correlative subordinating conjunctions: if … then, (al)though … yet/nevertheless, as … so, more/less -er…than, as … as, so …as, so…(that), such … as, whether … or, the…the, etc.

Also, two neighbouring clauses may be grammatically unlinked. For example, they may be separated in writing by a period/full stop (.) or a semi-colon (;) or a colon (:). But this does not mean there is no connection of meaning between them, it means rather, that the connection is implicit, and has to be inferred by the reader.

Complex subordinate sentences: Conditionals

Having seen what the main types of sentences in English are, what their structure, elements and behaviour is, let’s focus now on one particular type of subordinate sentences that are particularly important and also difficult for L2 learners. These are the sentences that express conditions and their difficulty comes from the tense usage, related to the type of condition that we want to express.

Conditional sentences can express all kinds of conditions. Some of them are likely to happen, some others are only hypothetical. The structures that are used to express that different degree of certainty are quite diverse. Grammarians have adopted technical names so that we can quickly identify the type of condition that the sentence expresses, but be careful since when teaching them we shouldn’t use those terms. They are only for us, teachers, and they are necessary for us to plan and grade our lesson. The learner’s task, again, is to grasp their usage and correct form by means of actively practicing them through activities and examples.

Conditional sentences consist of two clauses: main clause/result clause and subordinate clause/if clause and they are technically split into zero, first, second and third conditionals; going progressively from real to unreal conditions.

Zero conditional

The zero or “true” conditional is used to express general truths; situations that are always true if something happens. This use is similar to, and can usually be replaced by a time clause using ‘when’. E.g.

If I am late, my father takes me to school.

When I am late, my father takes me to school.

She doesn’t worry if Jack stays out after school.

The zero conditional is formed by the use of the present simple in the ‘if’ clause (subordinate clause) followed by a comma and the present simple in the result clause (main clause). You can also put the result clause first without using a comma between the clauses.

| Result clause | If clause |

| present tense | if + present tense |

| Most cats purr | if you tickle them under the chin. |

First conditional

They are often called the “future” conditional because both clauses refer to the future. They express possible situations in the sense that something will happen if a certain condition is met. E.g.

If I have enough money, I will go to Japan.

The First conditional is formed by the use of the present simple in the ‘if’ clause (subordinate) followed by a comma and the future simple with will in the result clause (main). You can also put the result clause first without using a comma between the clauses.

| If clause | Result clause |

| if + present | future |

| If it rains, | we will stay at home. |

| If he finishes on time, | we will go to the movies. |

| Result clause | If clause |

| future | if + present |

| We will go to the movies | if he finishes on time. |

| He will arrive late | if he doesn’t hurry up. |

In the 1st conditional we often use unless which means ‘if … not’. In other words, ‘…if he doesn’t hurry up’ could also be written ‘unless he hurries up.’

Aside from referring to possible situations in the future and other functions, we often use this conditional to express aspects of persuasion such as cajoling or negotiating and for giving warnings and making threats.

Persuasion: I’ll give you a surprise if you stop crying.

Warning: If you take that road, you’ll get lost.

Threatening: Unless you stop that right you, you’ll regret it.

Course books usually teach this conditional at an elementary or intermediate level.

Second conditional

The second conditional is often called the “unreal” or “hypothetical” conditional because it is used for unreal – impossible or improbable – situations. We use it to refer to or speculate about something that is (or that we perceive to be) impossible or ‘contrary to fact’. E.g.

If I had enough money, I would go to Japan.

Here, the condition is not likely to happen, we express a desirable condition more than a real one. In the example above, the truth behind the statement is that I don’t have enough money; this is the reality.

NOTE: Now it’s not a rule, but the verb ‘to be’, when used in the 2nd conditional, is conjugated as ‘were’.

I would lower taxes if I were the President.

If he were smarter, he’d know exactly what to do.

They would buy a new house if they had more money.

Conditional 2 is formed by the use of the past simple in the ‘if’ clause (subordinate) followed by a comma, and would verb (base form) in the result clause (main). You can also put the result clause first without using a comma between the clauses.

If they had more money, they would buy a new house.

OR

They would buy a new house if they had more money.

The 2nd conditional can refer to the present or the future.

| If clause | Result clause | |

| if + past tense | would + base form | |

| Present | If I had more patience, | I’d help him out more. |

| Future | If it got colder tonight, | I’d turn on the heating. |

The second conditional is sometimes used to give advice. E.g. If I were you…

Course books usually teach this form at a lower intermediate level.

Third conditional

Often referred to as the “past” or “unreal conditional in the past” because it concerns only past situations with hypothetical results. It is used to express a hypothetical result to a past given situation. E.g.

If I had had enough money, I would have gone to Japan.

Conditional 3 is formed by the use of the past perfect in the if (subordinate) clause followed by a comma and would have past participle in the result (main) clause. You can also put the result clause first without using a comma between the clauses.

If Alice had won the competition, life would have changed.

OR

Life would have changed if Alice had won the competition.

| If clause | Result clause |

| if + past perfect | would + have + past participle |

| If she hadn’t accused me of lying, | I would have been more sympathetic. |

| If he had know that, | he would have decided differently. |

We use this conditional to speculate about past events, and about how things that happened or didn’t happen might have affected other things. Also, we teach this conditional to express reproach and regret, and to give excuses.

Speculate: If he hadn’t wasted time, he wouldn’t have missed the train.

Reproach: You wouldn’t have had the accident if you hadn’t driven so fast.

Regret: I wouldn’t have left my job if I had known how difficult it would be to find another one.

Excuse (could also, somehow, express regret): I wouldn’t have been late if there hadn’t been so much traffic.

Course books usually teach this conditional at an upper intermediate level.

Inverted conditionals

So far the examples of conditional sentences contained conditions introduced by conjunctions in the subordinate or dependent clause. However, they are not the only means of expressing a condition.

Remember that when we want to emphasize or stress an important element in a sentence, we put it in first position. Sometimes, the important element is there in first place and doesn’t obey the natural syntax order of the sentence (SVO). When this natural order is inverted, we talk about inversion. Inversion is used to stress and emphasize elements in a sentence and requires a very high linguistic competence in their correct usage. That’s why these structures are usually introduced to advanced learners.

Let’s see how inversion can express conditions.

Compare:

If I had known the answer, I would have passed the test.

Had I known the answer, I would have passed the test!

The second sentence expresses a condition but the order of the subject and the verb is inverted. There is no “if” in the second sentence. Instead, the inverted order of the subject and the verb contains an implicit condition.

Variants on conditional sentences

Other ways of expressing conditional sentences are by means of expressions such as:

-Provided…

-On condition (that)…

- Unless…

-Supposing…

- As long as…

-Etc.

In a very informal way, conjunctions can also be omitted, since from context the conditional meaning is implied. E.g.

Eat more of that pudding and you’ll burst.

Keep still or I’ll cut your throat.

Syntactic peculiarities

1. Inversion

Inverted constructions

Inversion is a change in the normal syntax (word order) of a sentence. Normally English follows the strict SVO (subject, verb, object) order, but in the case of inversion the verb goes before the subject.

We’ve seen inversion in a conditional sentences when the “if” particle is omitted and is substituted by and inverted subject-verb order. For example:

Had I remembered his birthday, I would have bought a present.

However, inversion is not only to be found in conditional sentences. Whenever we want to stress or emphasize an important fact, we use this inverted formula. In formal and literary styles, the subject and auxiliary are inverted when negative adverbials are placed at the beginning of the sentence for rhetorical effect.

Take a look at the following example:

Barcelona is a beautiful city

S V

Not only is Barcelona a beautiful city, but it is also an important multicultural centre.

V S

Seldom have I seen him looking so miserable.

Hardly had we walked in the door when the phone started ringing.

No sooner had I reached the door than I realized it was locked.

Little did we knowhow difficult the journey would be.

How to teach inversion

Our advice once again will be to abandon the idea of starting our explanation talking about subjects and verbs to our learners. We should understand this structure, anticipate possible learning difficulties and errors and provide the most functional and practical explanation to our students.

Grammar books often provide multiple exercises of the structures with unconnected examples and different contexts. This can be useful but also somehow artificial and therefore not that easy to remember. Our example searches quite the opposite: provide a context which would be easy to remember and would give the learners the chance to practice the structure.

Imagine the following situation. A child has behaved badly. His dad is angry. What would he tell his son? Probably something like this:

Angry Dad!

“At no time did I say you could leave your bedroom! Seldom have I seen such a mess! I want you to tidy up and only then can you go and play with your friends! I want you back here by 7pm and on no account can you turn up late, covered in mud! Do you understand???”

Our example can be a little bit exaggerated, as it contains too many examples of the structure within a short paragraph, but it will definitely give the learner a natural context for the structure. That way it will be easier for them to assimilate the target structure first and to remember it later.

Now is maybe the moment to consider an interesting feature in language learning: the so called magic moment. A magic moment occurs in the classroom when we manage to transmit content in a thrilling and exciting way, which remains in the learners’ memories for a long time. This magic moment is often a result of a spontaneous situation that has aroused from something said or done in class that has provoked students’ acceptation, laugh and good atmosphere. Such moments are retained by the students, and so is the content that was involved in them.

By creating magic moments, we achieve much more than if we just try to make students practice lists of examples of the same kind. More creative activities, games, debates, chats and competitions can achieve that, so take advantage of them especially for “unattractive” and more difficult grammar issues.

2. Relative clauses

Uses of relative clauses

We use relative clauses to give additional information about something without starting another sentence. This additional information is related tothe main one in the sentence, therefore the name relative clauses. By combining sentences with a relative clause, your text becomes more fluent and you can avoid repeating certain words. In function, they’re similar to adjectives.

Types of relative clauses

There are two kinds of relative clauses: defining and non-defining relative clauses.

I. A defining relative clause identifies or classifies a noun:

- Do you know the guy who is talking to Will over there?

- The thing I liked best was the singing.

If we omit this type of clause, the sentence does not make sense or has a different meaning:

- Do you know the guy? (which guy?)

- The thing was the singing. (which thing?)

II. A non-defining relative clause adds extra information about a noun which already has a clear reference:

- The Mona Lisa was painted by Leonardo da Vinci, who was a prolific engineer and inventor.

- I wrote my essay on a photo, which was taken by Robert Capa.

If we leave out this type of clause, the sentence still makes sense:

- The Mona Lisa was painted by Leonardo da Vinci. (we know who Leonardo da Vinci was)

- I wrote my essay on a photo. (that’s the important information)

Sometimes, the use of commas marks a difference in meaning:

The athletes who failed the drug test were disqualified. (defining)

The athletes, who failed the drug test, were disqualified. (non-defining)

The defining relative clause tells us that only those athletes who failed the drug test were disqualified. The sentence implies that there were other athletes who did not fail the drug test and that were not disqualified.

The non-defining relative clause tells us that all the athletes (mentioned earlier in the context) failed the drug test and that all of them were disqualified.

Structure of relative clauses

Relative clauses uses follow whatever they qualify, so they come immediately after the main clause if they qualify the whole of the clause or the last part of it. Sometimes we can recognise relative clauses because they come after a relative pronoun or a relative adverb, but often it is only their sentence position and what the context tells us about their function that enables us to identify them.

Relative pronouns

- Who – used for people

- Which – used for animals and things

- That – used people or things, can be used in place of ‘who’ or ‘which’

- Whose – stands in place of a possessive form; used for possessions of people or things

Relative adverbs

- Where – used for places

- Why – used for reasons

- When – used for time

‘Whom’ is also included but it is archaic and not commonly used, so we won’t give it much attention.

Examples:

- I spoke to the man. He was in charge à I spoke to the man who was in charge.

- She drives a car. It is red àThe car which she drives is read.

- It is a football team. It has won the most cups à It is the football team that has won the most cups.

- Do you know the boy? His father is a politician. à Do you know the boy whose father is a politician?

- This is the shop. I buy my bread here à This is the shop where I buy my bread.

- Do you know I can’t go? Do you know why? à Do you know why I can’t go?

- My favourite time to go is summer. It is really hot àMy favourite time to go is summer, when it is really hot.

How to teach relative clauses

As always we follow the golden rule – BY EXAMPLES! As teachers, it is our job to have a list of examples up our sleeve just in case. We will achieve better results than exercises containing random examples if we can choose appropriate contents, such as a story for introducing it and a game for practicing it.

3. Reported speech

What is reported speech

When we speak, we often retell someone else’s words. Information or messages that were told to us and we need to transmit to someone else. In this case we use the so called reported speech or indirect speech, as opposed to the direct speech that is used to express our own ideas.

Reported or indirect speech is essential in everyday spoken English to basically “report” on what another person has said.

The use of reported speech is very important at higher levels, from intermediate to advanced. Students, at this point, are fine-tuning their communication skills to include expressing someone else’s ideas, as well as their own opinions.

Reporting verbs

The most common examples of reporting verbs used to report statements are said and told.

- He said he would come.

- He told me he would come.

However, there are a number of others: admit, beg, consider, propose, promise, suggest, confess, inform, notify, report, offer, recommend; to mentiononly a few of them.

If talking about commands, said and told are also commonly used, but command, ask, advise, request, and ask could also be used depending on the context.

- She told me to study for the exam.

- I advised him to obey his teacher.

- John requested me to lend him my text book.

Furthermore, when it comes to questions, the most common reporting verb is asked.

- She asked if you were alright.

And others are: inquire, want to know, wonder.

Reported statements

Reported speech includes some rather tricky transformations that need to be practiced a number of times before learners feel comfortable using them in everyday conversations.

When we report a statement, we often use a that-clause after the reporting clause (REPORTING CLAUSE + THAT-CLAUSE):

Tom: I don’t know her.

Tom told me that he didn’t know her.

That is often omitted after certain reporting verbs in informal styles:

Tom told me he didn’t know her.

In order to understand changes in indirect speech, we must bear in mind that words are always spoken in context: somebody says something to someone at a specific place and time. When we report something, changes are made to the original words in case there are changes in the context (people, place or time).

1) No changes are made to words referring to place, time or person if we report something at the same place, around the same time, or involving the same people:

Peter: I’ll meet you here.

Peter said he would meet me here. (reported at the same place)

Cara: My train leaves at 9.30 tomorrow.

Cara said her train leaves at 9.30 tomorrow. (reported on the same day)

Richard: I can help you, Stephanie.

I told you I could help you. (reported by Richard to Stephanie)

I told Stephanie I could help her. (reported by Richard to a third person)

2) Changes are made if there are changes in place, time or people:

Peter: I’ll meet you here.

Peter said he would meet me at the café. (reported at a different place)

Cara: My train leaves at 9.30 tomorrow.

Cara said her train leaves at 9.30 today. (reported on the next day)

Richard: I can help you, Stephanie.

Richard told me he could help me. (reported by Stephanie)

Richard told Stephanie he could help her. (reported by a third person)

I told Stephanie I could help her. (reported by Richard to a third person)

The following table shows some typical changes of time expressions in indirect speech. Bear in mind that the changes are not automatic; they depend on the context:

Direct speech |

Indirect speech |

| now | then / at that time |

| tonight | last night, that night, on Monday night |

| today | yesterday, that day, on Monday |

| yesterday | the day before / the previous day, on Sunday |

| last night | the previous night / the night before, on Sunday night |

| tomorrow | today, the following day, on Tuesday |

| this week | last week, that week |

| last month | the previous month / the month before, in June |

| next year | this year, the following year / the year after, in 1996 |

| five minutes ago | five minutes before |

| in two hours’ time | two hours later |

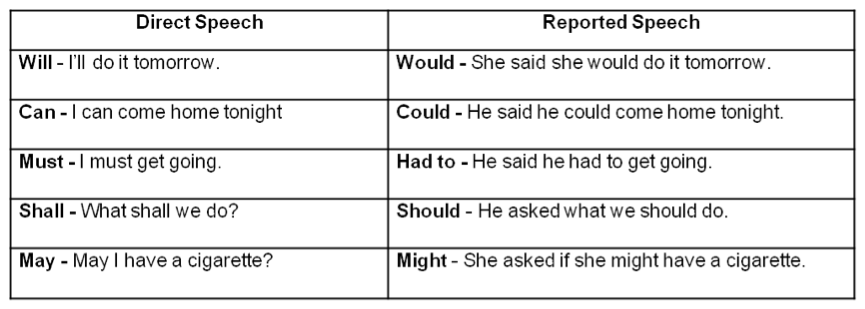

Reported modal verbs

Be careful with reported speech as the modals verbs have their own rules. See the table below.

Reported questions

When we report questions, there is no inversion of the subject and auxiliary in the reported clause (the word order is the same as in statements) and we do not use a question mark.

Yes/no questions

REPORTING CLAUSE + IF/WHETHER-CLAUSE (WITH NO INVERSION)

When reporting a yes/no question, we use if or whether:

Alex: Have you booked tickets for the concert?

Alex was wondering if/whether I had booked tickets for the concert.

Jasmine: Is there a wireless network available in the library?

Jasmine inquired if/whether there was a wireless network available in the library.

Peter: Is it cold outside?

Peter wants to know if/whether it is cold outside or not.

Peter wants to know whether or not it is cold outside.

Wh-questions

REPORTING CLAUSE + WH-CLAUSE (WITH NO INVERSION)

When we report a wh-question, we repeat the original question word (who, what, when, where, how etc.) in the reported clause:

Rebecca: Where do you live?

Rebecca asked me where I lived.

Tim: Who are you waiting for?

Tim wanted to know who I was waiting for.

A wh-clause can also be used to report exclamations:

Ivan: How funny!

Ivan exclaimed how funny it was.

We can use an indirect question after other reporting verbs when we are not reporting a question but we are talking about the answer to a question:

I’ve told you before why I don’t like shopping malls.

She didn’t say what time she would be back.

Reported commands

REPORTING VERB + SOMEBODY + TO-INFINITIVE

When we report an imperative sentence or a request, we usually use a to-infinitive structure:

Mother: Put away your toys, Johnny.

Johnny’s mother told him to put away his toys.

Teacher: Everybody, please stand up.

The teacher asked the class to stand up.

Mother: Don´t jump!

The mother asked the son not to jump.

Reported speech with and without tense change

There are no tense changes in indirect speech if:

1.- The reporting verb is in a present tense; this is often the case with simultaneous reporting or when the original words were spoken a short time ago and are still relevant:

Joanna: I have just arrived in Hanoi.

Joanna says she has just arrived in Hanoi. (reporting a recent telephone conversation; the reporting verb say is in present simple)

2.- The reported words are true at the time of reporting:

George: I‘m meeting Karen tomorrow.

George said he is meeting Karen tomorrow. (reported on the same day, tomorrow still refers to tomorrow)

If the previous sentence were reported like: George said he was meeting Karen the following day it would mean that the meeting had already happened.

3.- The reported words express a general truth:

Copernicus: The planets revolve around the sun.

Copernicus stated that the planets revolve around the sun. (it is a general truth)

If you compare to: Once, people believed that the earth was flat, then it’s evident that the reported words are no longer true; since people no longer believe that the earth is flat.

4.- The reported words refer to an unreal situation:

Mike: I wish I was a year older; then I could enter the race.

Mike wished he was a year older, so he could enter the race. (he is not older)

There is a tense change in indirect speech if:

1.- The reported words are no longer true or are out-of-date; this is often the case when we report something after the reference point of the original statement and the reporting verb is in a past tense:

Philip in 1980: I have never been to Brunei, but I’m thinking about going there. (the reference point of the present perfect and the present continuous is 1980)

When I met Philip in 1980, he said he had never been to Brunei, but he was thinking about going there. (reported years later; the reported words are out of date)

2.- We want to report objectively; when we do not know whether the reported words are true, and we do not want to suggest that they are:

Tim: Sorry, I can’t go to work this week. I’m ill.

Tim isn’t coming to work this week. He said that he was ill.

The following table summarizes the grammatical tense backshift in reported speech:

Direct Speech |

Indirect Speech |

| Present Simple | Past Simple |

| Present Continuous | Past Continuous |

| Present Perfect | Past Perfect |

| Present Perfect Continuous | Past Perfect Continuous |

| Past Simple | Past Perfect |

| Past Continuous | Past Perfect Continuous |

The past perfect and past perfect continuous tenses do not change since one can’t go a tense back.

In complex sentences, the past simple and past continuous may remain unchanged if the temporal relationship between the events in the clauses is clear from the context:

John: When I got home, I went to bed straight away.

John told me that when he got home he went to bed straight away.

Bill: I was reading a book when I heard the crash.

Bill said that he was reading a book when he heard the crash.

How to teach reported speech

When teaching reported speech, as usual, our suggestion is that you find a natural context, a situation or a story that would encourage students to use reported speech with connected statements as opposed to just random examples. Have a look at the situation below:

A man at the doctor’s. How would he report the doctor’s advice to his wife? Observe:

Doctor speaking to man:

You can’t drink any alcohol.

You’ll feel a bit drowsy after taking the pills.

You may feel tired after the treatment.

You must get plenty of rest.

You should come back and see me in 3 weeks.

Man REPORTING to his wife:

The doctor said I couldn’t drink any alcohol.

He said I would feel drowsy after taking the pills.

He said I might feel tired after the treatment.

He said I had to get plenty of rest.

He said I should go back in 3 weeks (notice no change in modal verb).

If you provide a similar practice for your students, along with an engaging introduction and the relevant explanation of the new structure, your activity will be more successful than if you just choose a gap fill activity or random examples.

4. Subjunctive

The subjunctive is a mood used to express necessity, unreality, wishes, hopes, and urgency; also being part of fixed expressions. It is usually difficult to notice, as it has no distinctive form in current English, only those that resemble other verb forms (base form or bare infinitive, past simple and past perfect). Bear in mind that the subjuntive is normally associated to an irregular conjugation of the verb, although it might not always apply.

Past subjunctive

The past subjunctive has the same form as the past simple tense except in the case of the verb to be. Traditionally, the past subjunctive form of be is were for all persons, including the first and third person singular. However, today I/he/she/it was is more common, while were is mainly used in formal styles and in the set phrase: if I were you.

The past subjunctive is used in subordinate clauses and refers to unreal or improbable present or future situations:

If I were you, I would apply right now. (I am not you.)

What would you do if you won the lottery? (You probably won’t win the lottery.)

It’s time the kids were in bed. (The kids are not in bed.)

I wish you were here. (You are not here.)

I’d rather your boyfriend stopped calling you in the middle of the night. (Your boyfriend keeps calling you.)

He looks as if he knew the answer. (He gives the impression that he knows the answer, but he probably doesn’t.)

Present subjunctive

The present subjunctive is identical to the base form or bare infinitive form of the verb in all persons, including the third person singular (no final -s). It is usually used in formal or literary styles:

*In certain set phrases:

I see what you mean. Be that as it may, I can’t agree with you. (even so, still)

Come what may, I will not resign! (whatever happens)

“I am a Jedi. Like my father before me.” “So be it… Jedi.” (it’s okay with me, I accept this)

I do not want to bore you; suffice it to say, we finally got a full refund. (it is sufficient to say)

*In exclamations that express a wish or hope:

Rest in peace!

Bless you!

God save the King!

*After adjectives such as IMPORTANT, ESSENTIAL, VITAL etc.

It is/it was + adjective + that can be followed by a present subjunctive if the adjective expresses importance or necessity or that something should be done:

It is vital that everybody get there before the examination begins.

It is desirable that Mr. Hanson hand in his resignation.

It is important that you be at home when the lawyers arrive.

It is essential that the car be waiting at the airport.

It is imperative that products be tested carefully.

In such sentences, the present subjunctive can be replaced with the less formal: should + infinitive:

It is vital that everybody should get there before the examination begins.

*After verbs such as INSIST, SUGGEST, RECOMMEND etc.

Mike insisted that I try his new muffin recipe.

I suggest that your cousin apply at once.

Carl was injured last week, and the doctor recommended that he not play in the next match.

Again, the present subjunctive can be replaced with: should + infinitive in less formal styles:

I suggest that your cousin should apply at once.

How to teach the subjunctive

Like all other grammar points, we recommend it being taught through simple context and examples.

Punctuation

1. Punctuation rules

Punctuation marks are symbols that indicate the internal structure of a written text, as well as pauses and intonation when reading it aloud. Punctuation marks may appear arbitrary in the different languages; still, they obey the internal logic of the text and avoid confusion of interpretation.

Consider the following sentence:

“King Charles walked and talked half an hour after his head was cut off”.

Surprising, isn’t it?

The same would make a completely different sense only with a small addition of a semicolon and a comma:

“King Charles walked and talked; half an hour after, his head was cut off”.

Before learning punctuation it should be noted that while there are some hard-and-fast rules, punctuation is a matter of personal style. However, you will notice that students learning English will try to impose their own language’s rules onto English, with the results sounding a little strange.

Below is the usage of the main punctuation marks used in the English language with some examples.

Full stop

A full stop (period in American English) is the punctuation marked placed at the end of each sentence.

Apostrophes

Apostrophes are used to show possession, form also known as the Saxon genitive. These are the rules for use of apostrophes:

1) With nouns (plural and singular) not ending in an –s: add –‘s

The children’s books, the people’s parliament, a Mother’s pride

2) With plural nouns ending in –s: add only the apostrophe.

The guards’ duties, the Nuns’ habits, the Joneses’ house

3) With singular nouns ending in –s: add either –‘s or an apostrophe alone.

The witness’s lie or the witness’ lie (be consistent)

Exception: ancient or religious names.

Jesus’ strength, Achilles’ heel

4) For common possession: add –‘s to the last name.

Janet and Jane’s house

5) Where possession is not common: add –‘s to each.

Janet’s and Jane’s homes

6) For pronouns: add –‘s to one’s, since possessive pronouns (its, his, hers) do not require an apostrophe

Parentheses

Used for additional information or explanation.

1) To clarify or inform.

Jamie’s bike was red (bright red) with a yellow stripe.

2) For asides and comments.

The bear was pink (I kid you not).

Colons

We use them before a list, summary or quote.

1) Before a list.

I could only find three of the ingredients: sugar, flour and coconut.

2) Before a summary.

To summarise: we found the camp, set up our tent and then the bears attacked.

3) Before a quote.

As Jane Austen wrote: ‘it is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife’.

4) To complete a statement of fact, where the colon is used in place of ‘i.e.’

There are only three kinds of people: the good, the bad and the ugly.

Semi-colons

The semi-colon is used:

1) To link two separate sentences that are closely related.

The children came home today; they had been away for a week.

2) In a list that already contains commas.

Star Trek, created by Gene Roddenberry; Babylon 5, by JMS; Buffy, by Joss Whedon; and Farscape, from the Henson Company.

Commas

Commas are used:

1) Between a list of three or more words; to replace the conjunction “and” for all but the last instance.

Up, down, left and right.

2) Before a conjunction: when “but” or “for” are used.

I did my best to protect the camp, but the bears were too aggressive.

3) When “and” or “or” are used the comma is optional.

The flag is red, white, and blue. [known as the Oxford comma]

The sizes are small, medium, or large.

4) To give additional information:

a. To indicate contrast.

The snake was brown, not green, and it was quite small.

b. Where the phrase could be in brackets.

The recipe, which we hadn’t tried before, is very easy to follow.

c. Where the phrase adds relevant information.

Mr Hardy, 68, ran his first marathon five years ago.

d. Where the addition is not necessary to the meaning of the sentence.

Mr Hardy, who enjoys bird watching, ran his first marathon five years ago.

e. Where the main clause of the sentence is dependent on the preceding clause.

If at first you don’t succeed, give up.

Even though the snake was small, I still feared for my life.

Hyphens

A hyphen is used with some prefixes and suffixes:

1) To avoid multiple letters.

Re-evaluate [ reevaluate ]

2) If the root word is capitalised.

Pre-Christmas, anti-European

3) With specific prefixes and suffixes.

Self -sacrificing, all-seeing, ex-wife, vice-chairman, president-elect

4) To avoid ambiguity or awkward pronunciation.

Un-ionised [unionised], re-read

5) Where a list of words each have the same prefix or suffix.

Pre-and post-recession, over- and under-weight

6) To form compound words

a. For clarity.

Sit-in, stand-out, Mother-In-Law

b. In compound adjectives that modify what they precede.

Blue-chip company, devil-may-care attitude, up-to-the-minute news

7) With fractions, numbers and initial letters:

a. With fractions and numbers between 21 and 99.

One-half, sixty-four, twenty-eight and three-quarters

b. Words that start with a capital letter

X-ray, T-shirt, U-Turn