Warning: include(C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php' for inclusion (include_path='.;.\includes;.\pear') in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

PREMISES FOR STUDYING LINGUISTICS & THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF HUMAN LANGUAGES I

UNIT 1: PREMISES FOR STUDYING LINGUISTICS

1. What is a language

One key aspect that sets humans apart from all other animals is their ability to use languages. Sure, birds tweet, cats purr, dogs bark and chickens squawk. However humans are the only living organisms to have developed a rich and complex set of rules and sounds that not only tell each other what we want and need, but how we feel and what we think. With language we can share ideas, make each other laugh or cry, manipulate, educate. Language allows us to be creative. Just as humans have evolved over thousands of years, so has language. It has gone from simple grunts and groans to thousands of unique and diverse symbols and tongues, used and spoken all over the planet.

Communicative purposes of languages

Language is the human form of communication. In the same way that birds tweet, cats purr, dogs bark and chickens squawk, humans gesture, speak and write emails/messages to each other. If you took a chicken from China and a chicken from Denmark, put them in the same chicken pen and had them squawk, would they understand each other? Well, this is a question that scientists have been pondering for decades, and they may never know the answer! What we could safely say is that if we were to put a Chinese and a Dane in the same room there may be some confusion. As humans have moved all over the world, language has changed dramatically. Not only do we have different words and grammar, but we even have altogether different sounds and alphabets.

As humans went from being primitive hunter-gatherers to sophisticated agriculturalists and merchants, the need to communicate with different people from different places grew and grew. The requisite for understanding and communicating in different languages is not just a modern one!

2. The origin and regulation of the English language

As an English teacher, it isn’t so important to have a profound knowledge of the history of the English language, but we should realize one thing: English is certainly a mongrel language. The English language as we know it originated with the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain. The Anglo-Saxons were a Germanic tribe and this gives English it’s German roots. From the north-east the Vikings arrived in long-boats and almost conquered the whole Island. They were eventually chased back across the seas but not without leaving us a bunch of interesting words such as anger, birth, slaughter, cake and leg. A few centuries later the French speaking Normans invaded from the South and conquered the whole of what is now modern day England. French became the language of the nobility in England giving us words like pork, fork, garden and candle. Add to the mix some Latin, Greek and Gaelic and we can really see what a cocktail English really is.

The most important person in the English language was without doubt a certain William Shakespeare. Not only did he lay the foundations for the standardisation of the English language, but he also invented around 1700 new words. If your students ever ask you why English is so complicated, BLAME SHAKESPEARE.

Watch this video so you can learn a bit more about the history of English:

Unlike other languages, there is no body that regulates the English language, but some institutions, such as the Oxford English Dictionary, do attempt to stamp some authority on the changes to the English language.

Varieties of English

There are several types of English: British, American, Australian, South African and even Pirate! If you’re curious as to how some of them sound, take a look at this video:

What type of English should I teach?

There is no right or wrong English to teach. As we are in Europe, British English is normally the standard at academic level. Teens are taught and assessed on British English. The most prestigious exams are set by Cambridge University. Maybe a businessperson may request an American teacher because they do most of their business in the USA, are planning a trip there to open up new markets, or may want to familiarise themselves with a type of accent.

In most cases, students will not care, or even realise what type of English you are teaching them. Your job as the teacher is to transmit your knowledge of the language to them, regardless of where your knowledge is from.

Does where you’re from make you a better or worse teacher?

While there are several types of English, there are even more accents! There is no correct or incorrect accent. At Oxbridge we have had teachers from Scotland, Ireland, Wales, England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Poland, Netherlands, Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela…

There is no easy or difficult, better or worse accent. It entirely depends on the students. While you shouldn’t need to disguise your accent, you should try to speak as clearly as possible. Normally it takes a few minutes for students to get used to your accent if they have never heard it before. If students tell you they don’t understand you, don’t panic and don’t take it personally. Tell them they will by the end of the class! It normally only takes about ten minutes for a student to adapt their ear to you. If you are a new teacher, it probably won’t be your accent that will give you problems. You’ll probably have them because you are not grading your language.

UNIT 2: THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF HUMAN LANGUAGES

1. Linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. Language could be described, in general, as a combination of sound (or movement; if one thinks about sign language and body language) and meaning. What linguistics does is describe and explain these features, dealing with three aspects of how languages behave: form, meaning and context.

There are many subfields of linguistics; including:

- neurolinguistics (which studies language processing in the brain)

- sociolinguistics (which studies the effect of society on how language is used)

- language acquisition (which studies how children and adults acquire a particular language).

- and applied linguistics (which uses findings on generalities about the language to “apply” them to other areas, such as language education and translation).

For our interest as English as a second language (ESL) teachers, general and specific knowledge on linguistics, language acquisition and applied linguistics is essential for our development, as it gives guidelines for assessment, for the choosing of learning activities, and for course planning and design.

2. Branches of linguistic study

On this Language analysis module of the course we’ll focus on linguistics, starting by understanding how it’s described.

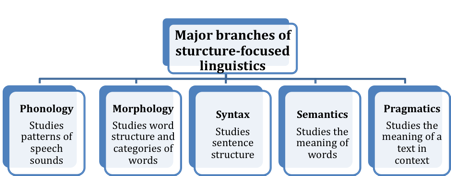

Major branches of linguistic study

The major branches of linguistic analysis are:

- Phonology

Phonology is the branch that deals with the study of the system or patterns of speech used in a language, which means that it studies speech sounds according to their function within the linguistic system. When reading about phonology you might also come across the concept phonetics. Take into consideration that the basic difference between these two is that phonetics studies speech-sounds without having in mind how they’re put together.

- Morphology

Morphology is the branch of linguistics dealing with the analysis of word structure.

- Syntax

Syntax is the branch of linguistics dealing with the organization of words into larger structures, particularly into sentences; equivalently: the study of sentence structure.

- Semantics

Semantics is the branch of linguistics dealing with the meaning of words and sentences.

- Pragmatics

Pragmatics studies how context contributes to meaning, or in other words: how meaning is inferred from the context. Unlike semantics, which examines meaning that is conventional or “coded” in a given language, pragmatics studies how the transmission of meaning depends on the context of the utterance, any pre-existing knowledge about those people involved, the inferred intent of the speaker, and other factors. In this respect, pragmatics explains how language users are able to overcome apparent ambiguity, since meaning relies on the manner, place, time etc. of an utterance.

A good explanation of pragmatics is given by the following text, depicting the difference between utterance and meaning:

When a diplomat says yes, he means ‘perhaps’;

When he says perhaps, he means ‘no’;

When he says no, he is not a diplomat.

When a lady says no, she means ‘perhaps’;

When she says perhaps, she means ‘yes’;

When she says yes, she is not a lady.

Voltaire

Secondary branches of linguistic study

When it comes to language learning and teaching, the most mentioned branch of linguistic study is grammar. Grammar, since it’s the set of structural rules that governs the composition of sentences and words in a language, comprises both morphology and syntax.

Another relevant secondary branch for our study is lexicology, which is the part of linguistics that studies words. Lexicology deals not only with simple words in all their aspects but also with complex and compound words, the meaningful units of language. Since these units must be analyzed in respect of both their form and their meaning, lexicology relies on information derived from morphology and semantics. Then, there’s also a third field of interest in lexicological studies, which is etymology –the study of the origins of words–.

3. Structural units of language

All branches of linguistic study are somehow related to specific structural units, which are described below:

Phonemes –> Phonology/Phonetics

Phonemes are speech sounds, which are the sounds that we actually pronounce while speaking. A phonemeis defined as the smallest contrastive linguistic unit that may bring about a change of meaning. For example, the difference in meaning between the English words kill and kiss is a result of the exchange of the phoneme /l/ for the phoneme /s/. Since this is a very common phenomenon, words like kiss and kill, which differ in only one sound, are called minimal pairs. ‘Sheep and ship’ and ‘leave and live’are also examples. If you ask your students to pronounce these, you’ll realize that they’re not that simple for English learners.

Morphemes and lexemes –> Morphology

A morpheme is the minimal grammatical unit in a language. It is not conceptually identical to a word, and the main difference between the two is that a morpheme may or may not stand alone, whereas a word, by definition, is freestanding. In that way, every word comprises one or more morphemes.

There’s a further classification of morphemes, for morphemes can either be free or bound. These categories are mutually exclusive, and as such, a given morpheme will belong to only one of them.

Free morphemes can function independently as words (e.g. town, dog) and can appear with other lexemes (e.g. town hall, doghouse). Bound morphemes, on the other hand, appear only as parts of words, always in conjunction with a root and sometimes with other bound morphemes. For example, un-, a bound morpheme, appears only accompanied by other morphemes to form a word. Most bound morphemes in English are affixes, particularly prefixes (e.g. a-, anti-, un-, des-, trans-) and suffixes (e.g. -able, -ation, -ly, -full, -s, -ing).

A lexeme is a unit of lexical meaning that exists regardless of the number of inflectional endings it may have or the number of words it may contain. It is a basic unit of meaning, and the headwords of a dictionary are all lexemes. To be more specific, we can say that a lexeme is an abstract unit of morphological analysis in linguistics that roughly corresponds to a set of forms taken by a single word. For example: run, runs, ran and running are forms of the same lexeme, conventionally written as run.

Clauses and sentences –> Syntax

A clause is the smallest grammar unit that can express a complete idea. A simple sentence usually consists of a single clause and more complex sentences may contain multiple clauses.

A sentence can be defined in orthographic terms alone, i.e. as anything which is contained between a capital letter and a full stop. Grammatically, it’s a unit consisting of words that are linked and grouped meaningfully to express a statement, question, exclamation, request, command or suggestion.

Texts –> Pragmatics

A text presents one idea in context and is defined as a complete and independent linguistic form.

4. Branches of linguistic study: Grammar

As it has been stated before, grammar is the analysis of how languages work; the study of their articulation, their lexical composition and form, the function of the words and the way they behave when linked together. We also refer to it as the structures of a language or just structures.

How to teach structures: Modern teaching methodologies

Historically, people have associated the learning of a language to learning its structure. For a very long time, language teaching was focused on students just learning grammar rules. However, modern language teaching methodologies have a different perspective. They prefer a more functional approach to learning a language. In this approach, a learner is encouraged to use the language rather than to know its structure.

Stated in a slightly different way, we’d say that language learning was associated with the analysis of it and now it’s much more related to its use in context.

When we analyze, we move in this direction:

which means: from form and meaning to function. Imagine, for example, that a student says ‘I like’ when trying to express that he or she likes something. We clearly know that that’s not a complete sentence because it doesn’t sound right; it doesn’t sound right, in this case, means the form is incorrect. Maybe our most instinctive answer to that comment would be asking ‘You like what?’ o ‘What do you like?’, since along with the form comes the meaning, and we can’t really make out what that person likes with that sole statement. Grammatically, one could explain that like, being a transitive verb, needs an object, and so one always likes something. But, what good would it do to give such a technical explanation of the error? The fact is that the student wants to express what he likes (which would be the function) and that he or she hasn’t acquired the structure to do so.

Since we want our students to learn how to use the language and not how to analyze it, our presentation to them should go in the opposite direction,

which means: from function and meaning to form, or, in other words, from what we want to express to how to do express it. In this case, form is merely an intrinsic characteristic of how to express something, and not the object of study.

So, what are functions, exactly?

Focusing on functions means not focusing on what the structure is, but what the structure is for and what we are able to express with it. Functions are now considered essential because the learner understands not just a formula, but how, when and in what context to use that formula. As teachers, we’d have to know what the structure is, how it works, when it is used, and what it is used for; in order to provide the best explanation and practice for our students.

Functions versus structures

To illustrate how this functional approach works, we’ll take an example of one particular structure and see how the same structure expresses different meanings and functions.

Take the following sentences:

- If you go to the concert, I’ll buy you a drink.

- If you touch the stove, you’ll get burnt.

- If you scratch my car, you’ll be sorry!

- If you study hard for this course, you will probably pass.

All of these sentences could be associated to a specific structure or grammar point, which is the 1st conditional. If you showed them to students and asked ‘What are these examples of?’ they’d probably answer ‘the 1st conditional’, instead of saying ‘real possibilities’ or the like. Most learners would be able to analyze and identify these statements structurally, but they might not understand what they express. This is why the function is so important!

The fact is that there is not a one-to-one match between form and function. On the one hand, a structure may have a number of different functions:

If you go to the concert, I will buy you a drink. (Promise)

If you touch the stove, you’ll get burnt. (Warning)

If you scratch my car, you’ll be sorry! (Threat)

If you study hard for this course, you will probably pass. (Prediction)

On the other hand, a function may be expressed by a number of different structures, as in these suggestions:

- Why don’t we go to the movies?

- Let’s go to the movies.

- Shall we go to the movies?

- We could go to the movies.

Then, the form-function relationship is further complicated by meaning, which can only be deduced from context. In isolation, the question ‘Do you play cards?’ could either mean ‘Can you play cards?’, or ‘Would you like a game of cards?’ depending on the situation.

Another example of the importance of functions is that, if you say to learners ‘today we are going to practice the Past simple tense’, they would probably think:

AH HA!!! PAST SIMPLE = ED

and they would say things like: I walked, talked, played, etc.

However if you asked a learner, ‘What did you do last weekend?’ More often than not, they will reply in the present tense, so they will say: ‘I go to the cinema last weekend’, ‘I walk to the shop yesterday’, ‘I play tennis with my friend last weekend’.

This is when we realize that if we only teach a formula, students won’t thoroughly understand when to use this formula. Thus, it’s important that we always try to teach functions… and form always comes along.

Grading the level of difficulty

However, form is much more important when it comes to language awareness, since there are structures that are much more complex than others, and that students need more time, experience and exposure to the language to process and register. If, as teachers, we know what’s behind our speech and we’re aware of the structures and vocabulary we use when expressing ourselves, then it will be easier for us to grade the level of difficulty of our expressions and also easier for us to communicate with language learners; especially beginners and intermediate learners. Grading our language, in that sense, means monitoring the structures and vocabulary we use so we match our speech production to the listening skills of our interlocutors, in order to achieve communication.

But aside from grading our language while speaking, one might also grade the level of difficulty of an activity. Actually, many textbooks and reference grammar books are organized according to grammar concepts. In this context, grading the level of difficulty means that, when teaching a particular piece of content, one starts with simple structures and progressively incorporates more complex ones.