Warning: include(C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php' for inclusion (include_path='.;.\includes;.\pear') in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

ACTIVITIES BASED ON MACRO SKILLS. WORKING ON STUDENTS’ SPEAKING SKILLS AND FLUENCY

UNIT 3: ACTIVITIES BASED ON MACRO SKILLS

To carry out communicative tasks, users have to engage in communicative language activities and operate communication strategies.

Communication strategies are a means of using your resources in order to fulfill the demands of communication in context and successfully complete the task in the most comprehensive and/or most economical way feasible depending on your purpose. These strategies should therefore not be viewed with a disability model – as a way of making up for a language deficit or a miscommunication; native speakers regularly employ communication strategies of all kinds.

Communication strategies are used during communicative activities, such as conversation and correspondence, and these are normally interactive. That is to say, the participants alternate as producers and receivers. In general, the language learner/user’s communicative competence is activated in activities involving reception, production, interaction or mediation (in particular interpreting or translating). Each of these types of activity is possible in relation to texts in oral or written form, or both.

Progress in language learning is most clearly evidenced in the learner’s ability to participate and engage in observable language activities and to operate communication strategies, and clearly not in how many grammar rules they have learnt.

A convenient way of describing language activities is determining the skills that are involved in each of them to give learners opportunities to develop them during class. So, it is specified that there are four macro skills we need for complete communication (both spoken and written): listening, speaking, reading and writing; and these are the categories of activities we’ll revise below.

1. Listening activities

In aural reception (listening) activities the language user receives and processes a spoken input produced by one or more speakers.

The purpose of this type of activities is to help students understand other English speakers, not only for the purpose of comprehension, but also so they may respond accordingly.

If you think about it, listening comprehension involves a lot more than simply understanding the meaning of the vocabulary and expressions used. Students must also understand the speaker’s accent and grasp his or her intention. So, it is clear that when we listen, we listen with a purpose and as we plan a listening activity, we have to make sure the purpose is clear.

Listening activities include:

- Listening to public announcements (information, instructions, warnings, etc.)

- Listening to media (radio, TV, recordings, cinema);

- Listening as a member of a live audience (theatre, public meetings, public lectures, etc.)

- Listening to overheard conversations, etc.

- Following instructions

- Answering true/false

- Detecting mistakes

- Guessing definitions (or unknown words)

- Answering comprehension questions

- Paraphrasing – retelling the information in a different way

- Interpretation

- If your listening is a song or a story, putting pictures in order

In each case the user may be listening:

- for gist (to grasp the main points or general information presented in the audio);

- for specific information (to grasp specific information, details that are relevant, important or necessary);

- for a sequence (to grasp information they will need to act on or orders they will need to follow);

- for specific vocabulary (to identify and remember a series of words, which are usually easily categorized);

- for attitude and opinion (to listen for what someone is really saying, not what they’re literally saying, but what they actually mean), etc.

And the following are some factors of listening:

Reduced forms

Reduction can be phonological (“Djeetyet?” and “Did you eat yet?”) and morphological (contractions like “We’ll”). These can cause students difficulties, especially those who have only been exposed to full forms of English.

Colloquial language

Students who have only seen or heard standard textbook type language will find colloquial language difficult. Idioms, slang and reduced forms are just some examples of this type of language.

Stress, rhythm and intonation

English is a stress timed language and can be a frustrating experience for some learners as many syllables can come spilling out between stress points. The sentence “The PREsident is INTerested in eLIMinating the EMbargo” with four stressed syllables, takes no time at all for a speaker to blurt it out. Also intonation patterns can be difficult to interpret for listeners as they contain subtle messages like sarcasm, insult, praise etc.

2. Speaking activities

In oral production (speaking) activities the language user produces an oral text, which is received by an audience of one or more listeners.

There are many reasons to give speaking tasks and activities to students:

Making the students have a free discussion gives them a chance to rehearse conversation, which occurs outside the classroom. For example having the students take part in a role-play at an airport check-in desk allows them to ‘get the feel’ of what communicating in a real world context is like.

Speaking activities provide feedback for both the teacher and the students. Teachers can see the progress of the students and what problems they are having. Students can see what type of speaking they are good at and what they may need to improve on.

Good speaking activities can be highly motivating. If there is full participation by all the students and the activity has been setup properly it can give the students a boost to their confidence and make for an enjoyable lesson. In turn this can increase student motivation.

Examples of speaking activities include:

- Public address (information, instructions, etc.)

- Addressing audiences (speeches at public meetings, university lectures, sermons, entertainment, sports commentaries, sales presentations, etc.)

- Reading a written text aloud;

- Speaking from notes, or from a written text or visual aids (diagrams, pictures, charts, etc.)

- Acting out a rehearsed role

- Singing

In interactive activities the language user acts alternately as speaker and listener with one or more interlocutors.Reception and production strategies are employed constantly during interaction. There are also classes of cognitive and collaborative strategies (also called discourse strategies and co-operation strategies) concerned with managing co-operation and interaction such as turn taking and turn giving, framing the issue and establishing a line of approach, proposing and evaluating solutions, recapping and summarizing the point reached, and mediating in a conflict.

Examples of interactive activities include:

- casual conversation

- informal discussion

- formal discussion

- debate

- interview

- negotiation

- co-planning

- practical goal-oriented co-operation

- role-plays: Students can create an imaginary dialogue between characters in the previous or related activity and act it out.

- compare and contrast: Students discuss the similarities and differences between their culture and that of their partner, or that of an English speaking country in relation to the theme of the lesson.

- debates: Assign different groups to represent each side of the argument.

- simulation: Like a Role-play but simulates possible real-life situation where the students are given roles, all the materials and props required to act out the simulation e.g. newspapers, graphs, news flashes, name tags, etc. Lastly the structure is provided for the simulation in the form of situations and problems which are given at the start and at different parts of the simulation getting the students to analyze and adapt to the new information as the simulation progresses.

And the following are some factors of speaking:

Affective factors

One of the major obstacles with speaking is that learners have to overcome the anxiety of making mistakes and blurting out things that may be considered wrong or stupid. Our job as teachers is to provide the kind of atmosphere that encourages student to speak freely and see mistakes and errors as a necessary part of the process of learning.

Pronunciation

Another one of the problems facing non-native speakers of English is pronunciation. It is usually the largest obstacle to overcome when trying to achieve fluency. Many non-native speakers have studied grammar for many years but are unable to speak like native speakers due to their inability to pronounce the sounds of words properly.

Accuracy and fluency

In spoken language the question many teachers face is: How can one decide between two clearly important goals of accurate (clear, articulate, grammatically and phonologically correct) language and fluent (flowing, natural) language? This of course depends on the focus of the particular activity or needs of the students.

3. Reading activities

In visual reception (reading) activities what the reader receives and processes as input are written texts produced by one or more writers.

The way in which we process (and therefore understand) written texts is often described as either top-down or bottom-up.

The bottom-up strategy of information processing uses knowledge of letter-sound relationships, word recognition and syntactic or contextual understanding of the text to make meaning of unknown material. The teaching of phonemic awareness and sentence structure skills can assist this type of processing.

In the top-down method employs vocabulary knowledge, background knowledge and social construction to make predictions and derive meaning from text. This type of processing is often easier for poor readers who might have trouble with word recognition but have knowledge of the text topic.

But the approach to teaching reading that is accepted as the most comprehensive description of the reading process is the interactive approach. The Interactive Reading Model, as developed by David E. Rumelhart in 1977, describes a model of the reading process and the way linguistic elements are processed and interpreted by the brain. It combines elements of both bottom-up and top-down approaches.

Interactive reading engages students in their texts and encourages critical thinking as they progress through a story. Teachers often begin interactive reading sessions by reading aloud to model the behavior they hope to inspire in student readers. Students are given positive examples to produce proper pronunciation and voice inflection. Then they are given the opportunity to practice what they have been taught, developing their vocabulary and their skills of oral presentation. English teachers might ask students to act out scenes of a play, a piece of prose or poem. They might be asked to punctuate their words with bodily actions, such as a fist in the air or a stamp of the foot. The auditory and kinesthetic components to interactive reading help students with varied learning styles.

Examples of reading activities include:

- Reading for general orientation.

- Reading for information, e.g. using reference works.

- Reading and following instructions.

- Provide a title

- Summarize

- Continue the story

- Preface the story (what happened before or after the chosen text)

- Discussion/debates

- Guess the content by the title

- Order the story

- Provide an ending

- Draw a picture

- Comprehension questions

- Identify vocabulary

- If characters are involved: describe the character, tell the character something, etc.

- Retell the text from another character’s point of view

The language user may read:

- For gist.

- For specific information.

- For detailed understanding.

- For implications.

4. Writing activities

In written production (writing) activities the writer produces a written text, which is received by one or more readers.

A reason for teaching this skill is reinforcement, since some student can benefit from seeing the language written down. This way the students can see and produce the structures of the words and it can also help them transfer the language to memory. Students often find it useful to write sentences using new language after they have studied it.

Another reason is varied learning styles. Some students are quick at picking up the language just by looking and listening. For the rest of us, it may take little longer to internalize and understand the language. It can be a good activity for these types of learners to avoid the rush of face-to-face communication.

Also, in some cases, students need to know how to put together reports for work, how to reply to advertisements and most importantly these days how to write using electronic media formally and informally. In general, writing as a skill.

If you assign a written task, always provide a model of it, an example of what you want the students to do. Let them analyze the text and then give them a task / scenario where they have to produce something similar.

Examples of writing activities include:

- Completing forms and questionnaires.

- Writing articles for magazines, newspapers, newsletters, etc.

- Producing posters for display.

- Writing reports, memoranda, etc.

- Making notes for future reference.

- Taking down messages from dictation, etc.

- Creative and imaginative writing.

- Writing personal or business letters, etc.

- Write a letter (email, letter of complaint, cover letter, etc.)

- Write an essay.

- Copy a letter or a paragraph.

- Dictation (very old fashioned)

- Description (of a photograph, image, etc.)

- Gap fill (very little communicative written practice is required here)

- Opinion about a text.

- Summary of a text.

- Make a post on a social media site or mock site in response to a specific issue or argument.

- Make an advertisement for a job, to sell something, for a new product, etc.

- Apply for things, filling in forms or making a registration (could be done online or using a pre-printed form made up for class)

Interaction through the medium of written language includes such activities as:

- Passing and exchanging notes, memos, etc. when spoken interaction is impossible and inappropriate.

- Correspondence by letter, fax, e-mail, etc.

- Negotiating the text of agreements, contracts, communiqués, etc. by reformulating and exchanging drafts, amendments, proof corrections, etc.

- Participating in on-line or off-line computer conferences.

Some factors of writing include:

- Orthography problems (use of upper or lower case)

- Punctuation (incorrect or no use of punctuation)

- Spelling

- Layout

- Language: lexical and grammar mistakes or errors

- Sentence structure: wrong syntax

- Appropriate register for the type of writing

UNIT 4: WORKING ON STUDENTS’ SPEAKING SKILLS

Normally when we want to know if someone can communicate in a language we ask Do you speak English? The question is not Do you write English or Do you read English. We might think of it as a nuisance, but if we read between lines, this questions evidences our conception of how important this skill is for communication. Added to that, for most it’s not the easiest one to develop and many students struggle to use communication strategies whilst speaking. So, how can we help students make good use of what they know to achieve fluent communication?

1. Objectives and characteristics of topic activities

Topic activities are activities that practice fluency. During topic activities, students are encouraged to give their opinion and express freely what they think. They are speaking activities, but not to the sole example of speaking activities, since any activity, no matter if it is a structure, vocabulary or topic, can be done in a spoken/oral way.

Topic activities refer to the type of communicative activity that is not based on a closed and guided practice, but offers stimuli to students to work on their fluency by referring to facts or expressing opinions and ideas about a range of different subjects.

2. Topic activities and levels

Topic activities suggest expressing ideas and producing language. Therefore, they are more present with higher levels. Still, they can be practiced at an elementary level, once the students have started to learn basic vocabulary and structures. It is very important, however, to introduce these kinds of activities from basic levels of learning as they bring variety and are a fun part of the class. Just because our students have a low level of English doesn’t mean they lack opinions. Topic activities help them learn how to express complex ideas in a simple way.

In Oxbridge, the higher the level of the learners, the more topic activities present in a lesson plan, which means the proportion increases with the level.Thus, S1 students have only structures and vocabulary activities that deal with basic functions, while P2 students have one topic based on current news which we presuppose interesting for them and easy to stimulate talking. On the other hand, structure activities are higher in number, there being 3 in each class.In P3 we reduce structures to two, and we increase amounts of topics. Vocabulary in all levels is represented by two activities for different issue and sub-issue.

In P4 and P5 level we plan three topic activities, one of which is based on a current event or news and the other two about different purposes: one of them can be dedicated to a specific purpose, the other one based on something of general interest.

3. What to consider when designing topic activities

A Topic activity should last 10-15 minutes, so make the activity engaging. Make sure that there’s a good flow in the class. Think of a topic activity that will be suitable for different types of students and different interests. Make the tasks progressively harder. A simple reading exercise is not enough to test students’ understanding. You need something to get students involved.

Some key points to remember:

- Have a clear objective

- Make engaging introduction questions or sentences

- Provide clear instructions for the target language practice

- Always include concept check questions (wrap ups)

- Select carefully your target language, and grade the explanations to it, making sure they’re simple enough to be understood. Provide examples in context and images if referring to something concrete. Record the audio so students can listen to it before class.

- Format your attachment as well. Clear tables, font and layout are imperative for a successful activity.

4. Ideas for creating topic activities

When creating a topic, the first stage is to decide which subject you would like your students to talk about. Of course that if you know your students well, you can take their likes and interests into account.

Always keep your students in mind when choosing a subject. It is them who need to be doing the talking and need to form opinions. If the subject is too obscure or unusual, your students may find it too hard to form opinions.

Keep your subject light-hearted. Taking about politics, war or the economic crisis may be current and relevant but possibly a little depressing and even boring to some. The aim of your class should always be to have fun, since engaged learners are active learners, so choose a funny and interesting topic to discuss.

Where can you get inspiration for your topic activity?

Nowadays the best source of information is the Internet. News websites such as BBC, CNN, the Guardian, EL PAIS (English version) have up-to-date news articles that can be adapted into interesting topics for students; but you can also use newspapers, magazines, personal experience, book excerpts, ted.com, TV quiz shows, word games, idioms… there are a lot of possibilities!

What can you write topics on?

Anything, as long as the students do the talking. Just make sure that the topic is interesting for everyone, not just for you!

5. How to motivate students to speak

As the objective of topic activities is to encourage conversation, activities must be fully geared to make students speak. You can’t always rely on a simple discussion. Often, if the subject matter is extremely interesting or controversial, your students may take charge and turn the activity into a raging debate. Equally as often however, the students will answer your questions without much interest and the conversation may stall.

Depending on the subject matter, students may feel uncomfortable giving their own opinion. Or, it could be possible that they don’t even have much of an opinion on that particular subject. We can’t always rely on a discussion or a question and answer activity to get the students talking. For this reason it is essential to include an ‘activating’ activity which forces students to participate in a fun way.

Creating a role-play activity is a good way to force students to speak. By assigning roles, we depersonalise the activity. Students are playing a role, and as a result, are not giving their own opinions. This will help them speak more freely and make things more controversial and interesting. Make role-plays as silly as you can; the funnier the better.

Opinion cards can be useful too for the same reasons as mentioned above. This way you don’t ask the students for their opinions, you can simply discuss a different range of opinions.

Debates can also be a fun way to get students speaking. Assigning a side for and a side against where the teacher is the chairperson normally makes the class a bit rowdy!

Other ideas are:

- Discussions and Debates

- Description of a picture/ situation

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Competition Games

- Role plays

- Physical games

- Craft games

- Card games (labels/ situation cards)

- Snakes and ladders

- Bingo

- Board Games

- Charades

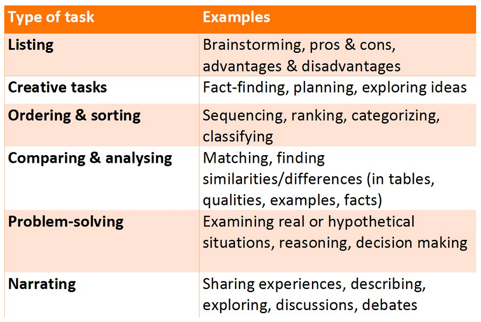

You can think about Topic activities as activities that include tasks to stimulate students to speak. Some examples of these tasks (according to the Task-based Language Teaching) could be:

Find more on topic activities practices in this BLOG POST by our teacher Vincent Chieppa.

6. Elements of topic activities (The Oxbridge model)

a. Objective or Summary

In this field we must state either the summary or the objective of our activity. As the objective for topic activities is to make students talk, this is what must be stated. If your topic activity contains a text and reading comprehension or a role play, this must be stated also.

A couple of examples of well-stated objectives (remember: specific, measurable, observable and achievable!) would be:

* Students to agree on where to have a friend’s surprise party.

* Students to discuss ways to protect the environment and come up with a list of 10 ideas they can start implementing today.

When writing your objective, make sure you meet the assessment criterion for it:

RRefers to skills/abilities that students develop during activity practice

b. Introduction

This is the point of the activity where we try to ENGAGE our students and lead them into our chosen subject.

My text is about hamburgers being made from different insects. I would introduce the topic in the following way:

- What is your favourite food?

- What is your favourite restaurant?

- How often do you eat out?

- What is the strangest food you have ever eaten?

- Would you ever eat a hamburger made of grasshoppers? Why?

In the previous example we have started talking about food in general and led nicely into the text.

Another equally valid introduction for the same text would be:

- How good is your diet?

- What types of food do you eat?

- How much meat do you eat?

- How expensive is beef in your town?

- What alternatives can you have for beef, if it is so expensive?

In this example we have taken the angle of healthy eating and beef shortage but have again led nicely to the text.

The introduction can come from any direction, but ultimately has to take your students in the direction of your subject and activity, whether it be reading, describing pictures… just write some engaging questions to help them warm up and start the conversation.

When writing your introduction, make sure you meet the assessment criteria for it:

| - Introduces the activity arguing its relevance; is engaging |

| - Questions are ordered conversationally |

| - No yes/no questions |

| - At least 3 questions relevant for the topic (& no typos) |

c. Activity

Probably a lot of topic activities that you have seen until now take the format of first a text, then a discussion, and then an activity that forces the students to produce language. But maybe you have also encountered topic activities in which students discuss dilemmas, or watch a video, or focus their attention on some sort of graphic resource. Try to think outside the box. Don’t go for the obvious.

Remember to ask yourself, is my topic interesting? Could we talk about this subject for 10 minutes? If the answer is no, pick another one!

Once you have picked your subject you’ve got to think about what you’ll ask students to do in the activity. If you pick a text, it is crucial that you adapt it. A text should be no longer than half a page long, around three normal sized paragraphs (16pt font!). This can mean that you might need to adapt your text from the original source.

Take only the key points from the article.

Discard quotes and peoples names, unless they are vital to the activity.

Try to make it timeless, but don’t force it. If it refers to specific events, it’s better to include dates.

Read over the edited text to make sure it all makes sense.

This is an example of a well-adapted article for a P5 level:

Volatile food prices and a growing population mean we have to rethink what we eat

Rising food prices, the growing population and environmental concerns are just a few issues that have organisations – including the United Nations and the government – worrying about how we will feed ourselves in the future.

Insects, or mini-livestock as they could become known, will become a staple of our diet. Insects provide as much nutritional value as ordinary meat and are a great source of protein, according to researchers at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. They also cost less to raise than cattle, consume less water and do not have much of a carbon footprint. Plus, there are an estimated 1,400 species that are edible to man. Things like crickets and grasshoppers will be ground down and used as an ingredient in things like burgers.

A large chunk of the world’s population already eats insects as a regular part of their diet. Caterpillars and locusts are popular in Africa, wasps are a delicacy in Japan and grasshoppers are eaten in Thailand.

(original source: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-18813075)

Have some interesting questions prepared for the teacher to ask that will stimulate conversation. Remember to ask interesting and open questions that should get the students talking EG:

- Why do you think the price of beef will rise so much?

- Will you miss beef from your diet? When?

- Would you ever eat one of these ‘hamburgers’? Why?

- Have you ever eaten an insect? What did you feel?

- What is the strangest food you have ever eaten?

As previously mentioned, we can’t always rely on questions to stimulate language production. It may be hard for students to form opinions on certain subjects. For this reason, it is essential to have another part to the activity that ACTIVATES the students, and forces them to talk.

Opinion cards, role plays and debates are great ways to get your students talking. You can be as creative and innovative as you like, as long as you make the students talk!

How can we make sure the students have understood the text?

You may read the text and check for understanding as you finish reading each paragraph (if it is a long text). If the text is short, you can read the text (at the same time you should read students reactions – check if they understand). After reading the text go through the target language (TL) to make sure the new words are understood and are now part of the lexicon that sounds familiar to the students.

Elicit answers from the students. Don’t panic and jump in. Allow students to take it all in. If you see that the students are struggling, guide them to the answer.

How would you elicit understating of the TL? – Usually we ask students to provide an example of the target language in context. You can also make them say the opposite (antonym), give a definition or mimic the target item.

Through Concept Checking you make sure your students use correctly the target item. Questions such as “Do you understand?” should be substituted by concrete examples that show that the students have understood and know how to use properly the TL. That doesn’t mean that questions like “Is there anything in the text you don’t understand?” should be completely eliminated; just that you should still check if they answer “no”.

And once you have done this, it means you can go on to the second part of the activity… discussions, debates, role-plays, etc.

When writing your activity, make sure you meet the assessment criteria for it:

| Overall: The suggested practice is creative and engaging |

| Content: Instructions are simple (& no typos) and teache- friendly |

| Activating Parts: Is divided in at least two parts that are progressively harder |

| Free practice: At least one makes students practice TL in a free form (debate, role-play, opinion cards, etc.) |

| Discussion questions are engaging and ordered conversationally |

| Engaging resources are used: video, graphic resources, images, short texts |

| Form: presentation is teacher-friendly and has consistent markers |

| Teacher’s Key: Activity description includes a key for teacher (if relevant) |

| Target language is stressed (bold, capital letters) in activity box, intro & wrap up |

d. Wrap-up

The wrap up is important for two reasons:

1) To review the TL and to make sure the students can use it correctly.

2) To conclude the activity and to prepare the transition to the next activity. Provide a few questions that gently sum-up the activity and bring it to a logical end.

When writing your wrap-up, make sure you meet the assessment criteria for it:

| - CCQs: They’re all Concept Check Questions (CCQs) that refer to Target Language (TL) |

| - At least 3 diverse questions |

| - Relevance: Questions are specific and refer to difficulties students might have had |

| - Doesn’t introduce new info |

e. Target language

The target language (TL) are interesting words or phrases that we want the students to be aware of. They can be any part of speech (e.g. nouns, verbs, adjectives), phrasal verbs or idioms. Pick six to eight pieces of target language that you want your students to study.

Pick words that are unusual, but useful. There is no point in teaching your students words that they will never use. Keep the level of the students in mind. You can be freer with TL selection for higher levels.

In case you choose not to use a text, you can always introduce TL in questions, tables, titles, lists; there are many ways of introducing new TL.

After you have chosen the words and included them in the activity, you will need to insert the TL into the Oxbridge system. You will be asked to provide a definition and an example of the TL in use. Don’t give a dictionary definition. In your own words, find an easy way to explain the TL. When giving an example, use the TL in the context that it appears in the activity.

If you want students to get the best from your TL, record an audio example. You will be helping their pronunciation a lot! There are many free audio recording programmes but we recommend you to download Audacity for recording from: http://audacity.sourceforge.net/. You can also use a very useful website that saves you having to download a program: http://www.recordmp3.org/

When filling in the Target Language section, make sure you meet the assessment criteria for it:

| - Is conformed by the most relevant words/phrases necessary to understand and practice the activity |

| - The words/phrases are adequate for the level |

| - Definitions are simple and clear (& no typos) |

| - Examples help students deduce meaning by context |

| - Audio (loud and no background noise) |

| - Image if relevant for word |

| - Maximum 8 words |

f. Attachments

Your attachment is the part that you will be using with learners to activate the TL, therefore its presentation and layout has to be perfect!

Of course, make sure that if text is included, spelling and punctuation are immaculate.

Speaking of the text, choose a bigger font so that learners don’t struggle to read it.

Highlight the TL either in bold or in CAPITAL letters.

If you are including images, charts, graphs, we recommend using a table with the same size of the images.

When producing your attachment, make sure you meet the assessment criteria for it:

| - Overall: Is clear enough to teach the activity even with little instructions and provides enough practice of the TL |

| - Content: Sample of authentic speech (video) with transcript is provided to introduce the news or topic whenever appliccable |

| - If a text, there are typos and it’s easy to read |

| - Form: Pictures and word lists are included in tables. The attachment is well aligned and sized, the quality of the pictures is good and with no water marks. If matching activity, rows are evenly distributed |

| - If relevant, there is a copy for the teacher and for the student |

| - Wysiwyg is used wisely to stress target language and relevant information |

| - The attachment is named properly. |