Warning: include(C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

Warning: include(): Failed opening 'C:\\Inetpub\\vhosts\\spanico.es\\httpdocs/patch.php' for inclusion (include_path='.;.\includes;.\pear') in C:\Inetpub\vhosts\spanico.es\httpdocs\wp-content\plugins\hana-code-insert\hana-code-insert.php(138) : eval()'d code on line 1

THE SYLLABUS. LESSON PLANS

UNIT 1: THE SYLLABUS

A common question in English Language Teaching (ELT) is ‘How should I structure classes’? In addition, many wonder how they can be good teachers if they have to improvise all the time. The following will provide you suggestions on how to give successful classes even when improvisation stares you in the face.

1. What is a syllabus

One of the most useful tools a teacher can possess is a well-structured syllabus. As teachers, we should be capable of developing learning plans and syllabuses. There are several ways in which we can do that, but the basic idea is that we need to know what the students know and don’t know (identify their needs) to determine what they have to learn (specify objectives).

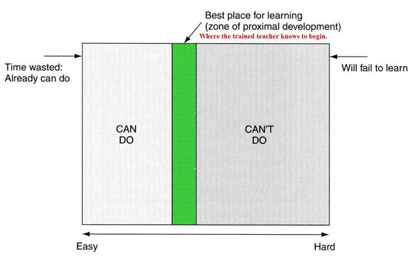

Analyze the following diagram thinking about how syllabuses are planned:

Picture the “CAN DO” part of the diagram as the proficiency level of students and the “CAN’T DO” as the body of knowledge and skills that they still haven’t acquired. If too difficult tasks were introduced in the learning activities, thus challenging students too much, they might feel anxious and overwhelmed; whereas if the level of challenge were too low they would be bored. The teacher’s role is, therefore, to strategically help students during activities so what they can achieve in that moment with the teacher’s help and/or the help of their peers they eventually do by themselves, increasing their level of competence.

Our choice of teaching strategy and learning programs is influenced by the teaching methodology we adhere to; which as you already know has to do with a particular way of understanding how people learn, specific teaching and learning goals, organization of the content, teacher’s and students’ roles, interaction conditions, types of activity, etc. There are many ways of categorizing teaching methodologies, but for practical purposes we’ll focus on two of them: learner-centered and curriculum-centered environments. The basic difference relies on using what the students know –their actual level of proficiency– as a starting point to establish the course’s contents or using general standards to do so i.e. level descriptions as those from the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). This means that in a learner-centered environment we use students’ knowledge to specify needs, determine objectives, define content, and select and create activities; whereas in a curriculum-centered environment we use level descriptors.

Regardless of the structure that corresponds to your belief system, you will develop an outline and summary of what will be covered in the course, a schedule of due dates for assignments, grading policy for the course, etc. That means developing a syllabus.

2. Elements of a syllabus

A syllabus must at least contain:

- Learning goals and objectives of the course

- Content distribution per session

- And distribution of classes within a period of time (dates).

The following is an Oxbridge example of content distribution for a General P4 course syllabus:

Class 1 of 96

Structure – Issue: Expressing quantity

Sub-issue: Pronouns: someone, anybody, everything, nowhere, none. Every, each, all. One and ones, substituting nouns.

Vocabulary – Issue: Trade, economy and finance

Sub-issue: Business and finance

Structure – Issue: Describing and defining objects and actions: adjectives and adverbs

Sub-issue: Compound adjectives (a good looking man, blue eyed girl)

Topic - Issue: Lifestyle

Sub-issue: Affairs and relationships

Vocabulary – Issue: Tourism

Sub-issue: Travels

Class 2 of 96

Structure – Issue: Expressing likes, dislikes, preferences and options

Sub-issue: Preferences and suggestions with “would” and “rather, better, sooner, prefer, etc.”: I’d rather, You’d better, I’d sooner, She’d prefer, etc.

Vocabulary - Issue: Idioms and Expressions

Sub-issue: Action verb idioms

Topic - Issue: Lifestyle

Sub-issue: Health and fitness

Structure – Issue: Describing and defining objects and actions: adjectives and adverbs

Sub-issue: Adjectives and participles (adjectives with -ed / -ing endings)

Vocabulary – Issue: Arts

Sub-issue: Cinema

Class 3 of 96

Structure – Issue: Expressing emphasis and focus

Sub-issue: Non finite forms: simple infinitive (be), perfect infinitive (have been), simple gerund (being),perfect gerund (having been)

Vocabulary – Issue: Trade, economy and finance

Sub-issue: Sales and acquisitions

Structure – Issue: Describing and defining objects and actions: adjectives and adverbs

Sub-issue: Order of adjectives

Topic - Issue: Lifestyle

Sub-issue: Worlds cultures and traditions

Vocabulary - Issue: People

Sub-issue: Physical appearance

Class 4 of 96

Structure - Issue: Joining ideas (Making complex sentences )

Sub-issue: Clauses beginning with ‘what’ and ‘whatever, ‘whichever’, ‘whoever’, ‘wherever’ or containing them.

Vocabulary – Issue: Word-building

Sub-issue: Phrasal verbs: Put

Topic – Issue: Lifestyle

Sub-issue: Entertainment and social life

Structure – Issue: Expressing comparison

Sub-issue: Intensifiers in comparison: much, a lot of, far bigger, much more, far less. The … The (The sooner, the better).

Vocabulary - Issue: The world of work

Sub-issue: Office basics: Expressions related to being late for work

3. Different types of ESL syllabi

Different syllabi are used for different courses. Examples of courses are:

- General English courses

- English for Specific Purpose (ESP) courses (Business English, Medical English, Legal English, etc.)

- Intensive English courses (concentrates more sessions in a period of time)

- English courses for particular ages (Kids & Teens)

- Courses for specific categories only (Vocabulary, Grammar, etc.)

The course syllabus is usually set by the particular school or institution, and sometimes it is indirectly set by textbooks; especially if that’s the only available resource for the teacher.

4. The importance of syllabi

Syllabi are important because they: state objectives according to the purposes of language learning, they ensure consistency between classes, and they specify what must be taught.

A lesson can be very well planned and successful, but if it does not belong to a major organisational category (course syllabus, curriculum) we don’t have enough information about the “before and after” of that particular lesson plan. In that sense, the syllabus gives the context for each and every class.

Textbooks can be a starting point, but, although it is tempting to just follow them, they shouldn’t be the only resource. While using textbooks, teachers tend to get stale; not to mention how much it harms their professional development having the easy way out and not stopping to think about how to adapt activities to their students’ individual needs.

These consequences, along with the fact that preparing good activities implies a lot of work, are reasons for Oxbridge to distribute and share lesson plans and activities amongst their teachers. The workload for one teacher in lesson planning is such that if collective work is not considered, teachers often find the task impossible and end up taking the easy way: a textbook.

Anyone can become a course author and activities editor knowing what the purpose of the course is and its target students. That is why knowing what is behind a syllabus is very important.

UNIT 2: LESSON PLANS

1. What is a lesson plan

The minimal unit of a planned course is the concrete lesson and in order for a lesson to go well we need a plan of what we’ll do and how we’ll do it, and that’s a lesson plan.

2. Elements of a lesson plan

What must we include in a complete session?

The answer to this question determines the success (or failure) of any single English class.

A complete session should provide all the necessary tools to achieve one or more communicative goals with their right timing.

According to the Oxbridge model, a lesson plan should enable the teacher with all the necessary tools for successful learning; consisting on a well-studied incorporation of vocabulary, topic and structure activities according to each level with a correct pace and timing. Each of these activities has to:

- be based on an engaging subject

- match the student’s abilities

- contain proportional and realistic target language

- have guided steps for the practice of this target language

- include aids to stimulate and motivate the students

- and contain a logical conclusion with error analysis.

The class’ duration determines both the number of activities and communicative goals/learning objectives. In Oxbridge, lesson plans normally include 6 to 8 activities and each activity is planned to last 10 to 15 minutes. Since learning sessions are normally between 60 to 90 minutes, these lesson plans are enough for one class. However, for longer sessions, those that are 120 minutes or longer, we use activities from two different classes.

An easy way of creating the structure of a lesson plan, including all its elements, is a table like the one that follows:

Type of activity |

Objective(s) |

Brief activity description |

Timing |

Ice breaker |

- Build rapport- Activate prior knowledge | 1. Questions for them to describe their moods and reasons behind them | 5 min |

TL review |

- Recall previous learning experiences; activate prior knowledge- Detect what they remember and conclude why they do so | 1. CCQs on TL of previous classes | 5 min |

Grammar |

- Use relative clauses accurately to give extra information of their friends and possessions | 1. Show examples of relative clauses in context2. Ask them to produce similar sentences3. Students ask each other questions and they answer using relative clauses | 15 min |

Reading |

- Deduce meaning of vocabulary items through context- Rephrase and summarize ideas found in the text | 1. Read text2. Go over TL words3. Ask reading comprehension questions | 15 min |

| … | … | … | … |

| … | … | … | … |

3. Stages and elements of a class

In his book, ‘How to Study English’, Jeremy Harmer states that lesson plans should include the following elements:

- Engage: capturing students’ interest in the topic or task

- Study: this point in the teaching sequence is when students’ attention is focused on the new construction or target language. Students work out the rules or imitate patterns to practice the target item (practice is normally restricted to specific grammar issues or vocabulary items)

- Activate: communicative uses of language in as free a manner as possible. Usage of whatever language resources they have to complete a task (not necessarily the restricted practice of specific grammar or vocabulary item)

These stages may be present more than once in a lesson. They could also come in any order – there are no hard and fast rules.

Another formula for staging a lesson plan is the so-called PPP – Presentation, Practice and Production.

- Presentation – introducing the target language in a natural context

- Practice – giving the students the opportunity to use it in a limited framework

- Production – providing the opportunity for the students to use the language in a freer way.

4. Activities

4.1 Premises for choosing activities

When considering which activities to include in a particular class, a teacher must think about:

- the students’ level/levels,

- their specific needs,

- what motivates them

- and how the activities relate to the syllabus and objectives.

Though students may have started classes with a specific goal in mind and have the requisite motivation they might still be distracted, tired or respond better to some types of activity than others. Also, teachers must assess the relevance of their activities bearing in mind the syllabus, sequencing and objectives.

4.3 Categories of activities

Activities can be classified in:

- Type of language that’s practiced, i.e. oral or written language;

- Language skills that are practiced, i.e. writing, reading, speaking or listening; vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar or spelling activities;

- Or factors of language that are being developed; i.e. accuracy or fluency

At this point we should mention that sometimes oral activities are confused with activities to develop speaking skills solely, but developing speaking skills can be achieved through any activity category: students develop speaking skills through actively speaking in Oxbridge’s topic activities, but also through the vocabulary and the structure ones. Oral activities also develop other skills, aside from speaking skills, directly or indirectly. For example, they directly develop listening and understanding skills, since speaking is a consequence of a stimulus, often an auditory one; or they might indirectly develop writing and reading skills, as some of the activities include them in some of their phases.

In any case, depending on the category, each activity plays a role in developing particular language skills. As a result, its objectives (content-based or student needs-based) have to be specified.

4.2 Specifying objectives

Learning objectives and learning outcomes are two essential components of any successful planning and design of a course, a unit or a lesson plan in teaching. The presence of distinction between learning outcomes and learning objectives is a point of debate, but scholars who do make the distinction suggest that learning outcomes are a subset or type of learning objectives.

In this sense, learning objectives tend to be more general than learning outcomes. They describe the overall goals of a unit or a course or show what the teacher will do (the aims or teacher-driven objectives). Normally these objectives are determined by a needs analysis and here are some examples:

- Students to use past tenses to talk about the things they used to do when they were children.

- Students to produce basic household vocabulary to describe their own home.

- Students to list the contexts in which formal and informal forms are used (or use the correct form in the appropriate context).

A learning outcome, on the other hand, is a statement of what a learner will be able to do after a learning experience, such as a class, course or program. Learning outcomes need to be specific, measurable, observable and achievable in relation to the lesson, unit or course of study being used. When learning is clearly defined and shown by outcomes, learners are more likely to experience success.

It is important to make sure the objectives are clear and assessable, and not vaguely written as shown below:

- Students will understand how to use possessive pronouns.

- Students will know how to talk about their personal life.

- Students will practice formal and informal greetings.

These outcomes may seem good enough but when it comes to assessing and measuring… how can you measure understanding and knowing? When specifying learning outcomes think of something more like:

- Students will use possessive pronouns accurately.

- Students will answer correctly at least three questions about their personal life.

- Students will demonstrate that they know the difference between formal and informal greetings.

What outcomes are NOT: Outcomes are NOT the things that students do during the lesson. Outcomes are NOT things that the student understands or appreciates.

Every time we come up with a lesson plan, learning outcomes should be specified for each and every activity that will be part of the class. In order for these objectives to be pedagogically accurate, Bloom’s Taxonomy can be used.

Incorporating Bloom’s Taxonomy into lesson objectives will enable both you and your learners to visualize the ‘bigger picture.’ More importantly, we as teachers can use the cognitive part of the Taxonomy to understand what exactly we are asking learners to do in class.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is based on 6 distinct levels shown graphically in the following pyramid and defined in the table that comes after:

Category |

Definition |

Example verbs/ Key words |

Example activity |

Example objective |

1. Remembering (Knowledge) |

Defining terms and correctly identifying the meaning of certain words.. |

|

Recalling or retrieving previous learned information | Learners will be able to match vocabulary items to the correct definitions |

2. Understanding (Comprehension) |

Comprehending the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words. |

|

True or false activities and reading comprehension questions. | Learners will be able to answer comprehension questions after the reading of a text |

3. Applying (Application) |

Learners apply concepts and techniques that they learned in class to authentic situations. |

|

Using a piece of target language in a different context correctly. | Learners will be able to use target language in contexts differing from originally given example |

4. Analyzing (Analysis) |

Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Learners can uncover patterns and discover meaning by differentiating information. |

|

Grammar boxes that require learners to deduce rules. | Learners will be able to deduce the grammar rules for using who and whose in relative clauses |

5. Evaluating (Evaluation) |

Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials. At the evaluating knowledge level, teachers are starting to really challenge learners to build up high-level critical thinking skills. |

|

Making recommendations based information given during the lesson or an activity. | Learners will be able to recommend the other students suitable travel destinations based on their preferences |

6. Creating (Synthesis) |

Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure. Learners are required to create some kind of tangible product. |

|

We typically see such activities at the end of a course book unit, in which all of the input leads to the production of a poster or a set of rules, or some such interpretation of what has been learned. | Learners will be able to create an outline of a marketing campaign |

This system can be used at all levels of the teaching process when thinking about what we want students to achieve, and it can be a valuable tool in ensuring you are meeting the needs of the learners and of the course or program of study.

Depending on the program of study one can have more or less freedom at the moment of choosing the type of activity to do in class. So now, let’s understand a little bit more about the program of study you have been observing during this TEFL course: the Oxbridge model.

Find more on Bloom’s Taxonomy in the following links:

A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing

5. The Oxbridge model

According to the Oxbridge English Teaching System, each session has to include one or more activities from one of the three main categories that it specifies:

- Structures

- Vocabulary

- Topics

This mix of activities ensures that students are engaged and stimulated throughout the class.

Children in particular need to have different tasks and activities in quick succession as they generally can’t concentrate on one thing for a long time, but this also extends to adults. Think of people who attend classes during their lunch break or after a hard working day! The last thing they want to do is to be bored to death with gap-fill activities or writing an essay!

The number of each of these types of activity is dependent on the level of the syllabus and therefore the class. Normally, more accuracy activities (i.e. structures and vocabulary) are present in lower levels and more fluency activities (i.e. topics) are included in higher levels.

The order of elements is also established according to the level of the class. It might be too aggressive to start with a Topic in an elementary level, but maybe not that demanding for an advanced student. Although we normally start the class with either a Structure or a Vocabulary activity, the teacher can change that order depending on each particular group; based on whatever the teacher considers might have a better result considering the students being engaged, motivated and actively learning.

This is an example of a possible order and timing for a 90 minutes intermediate level (P3) class:

Quick questions 5 min.

Structure activity 1 15 min.

Vocabulary activity 1 10 min.

Topic activity 1 20 min.

Structure activity 2 10 min.

Vocabulary activity 2 15 min.

Topic activity 2 10 min.

Conclusion and analysis 5 min.

5.1 Structure activities

These provide learners with the required grammar patterns for learning the English language and using it correctly. Structures are a very important part, and it’s often thought that they aren’t taught enough because of the subtle way they are presented. For example, we would never introduce a structure activity by saying:

“The structure we are going to study today is the present continuous tense”

Instead, our introduction would guide the learner to the usage and function of the structure and its practice after that.

e.g.

“Every day I go to work. Today I am working in a new project. Now, I am thinking of my next activity. In that moment I am writing my ideas. What are you doing right now?”

After that, a brief explanation (if necessary) and we would ask some concept check questions. This would then be followed by active practice of the tense, maybe with visual support being offered to the learners.

Although we never introduce a grammar point directly, we do reinforce its usage and provide explanations and a summary at the end of the class. Guidance and stimulus is the key factor to performing the structure activities correctly.

There are often more structure activities in the Oxbridge model than other types, but (as it has been explained before) this is not inconsistent with the fact that the teacher is always prompted to focus on oral practice. Also, that doesn’t mean that for Oxbridge the structure activities are the most important ones, but definitely the most necessary to help students become accurate, along with the vocabulary activities.

In Oxbridge, most structure activities are organised by their function and meaning/form (issue and sub-issue). Again, the level of difficulty of the structure activities increases with the stages of production of the students (speaking level, grammar level). Lower levels’ goals are to give the students the basic and most commonly used structures for a successful communication. The higher the level, the richer the structures and grammar patterns we expose the students to.

Example of a structure activity order:

Issue: Expressing actions in present

Sub-issue: The present simple tense

Sub-issue: The present continuous tense

Sub-issue: The present perfect tense

5.2 Vocabulary activities

These are targeted at improving students’ pronunciation and providing students with the necessary lexicon for the purposes of full communication.

They are organised according to semantic fields (issue and sub-issue) and the vocabulary activities are planned out to give the necessary vocabulary for the objectives of each level. They go from items related to the immediate surrounding for beginners (the house, the world of work, travels, hobbies, family, etc.) to more complex and diverse items that include terminologies associated with particular professions, phrasal verbs, idioms, and proverbs. The higher the student’s level the broader the vocabulary’s semantic field.

An example of vocabulary order could be:

Issue: The world of work

Sub-issue: The career ladder

Sub-issue: Work injuries

Sub-issue: Jobs and professions

5.3 Topic activities

Topic activities could be considered as the cherry on the cake for a teaching method, as they are the ones that will allow the learner to improve their fluency and give them the chance to use whatever language resource they choose to complete the task. This relates to the ‘Activate stage’ defined by Jeremy Harmer.

Topic activities should be engaging, stimulating and fresh. The idea is that they are something to remember and talk about after the class. If that result is achieved, you can relax, as you’ll have happy, successful learners.

It is important to not limit topic activities solely to activities developing speaking skills. As the structure and the vocabulary ones, topic activities are performed orally, but they develop different skills directly and indirectly according to the level.

Unlike vocabulary and structures activities, topics aren’t usually classified or organised into issues and sub-issues. Though there are exceptions with some topics for specific purposes, such as Business English, when we want the students to be acquainted with particular cases with a business focus.

In case of Business English, an example of a possible topic order is:

Issue: Entrepreneurs and leaders

Sub-issue: Richard Branson and the Virgin empire

Sub-issue: Apple vs Samsung

In these cases we provide a case study, often a SWOT analysis, role-plays, video clips and facts etc.

5.4 Quick questions

Quick questions are a particular aspect of the Oxbridge English Teaching System. They are a warm up activity used in each and every class, level and course. They are one of the trademarks of Oxbridge and a core part of its identity.

Quick questions fill the first 2 minutes of the class with something meaningful and different rather than just making small talk and asking about how the students are. That way no single minute from the class is lost and we change students’ linguistic chip into English. Aside from that, there are extra advantages to quick questions; one being that students are exposed and practice inversion in questions and answers, which is not an easy thing to master.

5.5 Wrap-up/Conclusion

Usually this is not prepared as a separate activity, however in the last 3-5 minutes of the class the teacher should revise the target language or tasks performed in class and analyse some of the common mistakes. Such practice gives students a feeling of closure and they can leave the class with the clear idea of what was learnt and practiced in class. As new language (vocabulary and structures) is usually presented in a subtle way, the students may have the feeling that they haven’t learnt or practiced enough grammar or vocabulary. This definitely won’t be the case if the teacher gives a summary of the class as a conclusion or wrap up.

Also, taking into consideration what the students answer, the teacher can assess his/her teaching method and activities based on how much of the class’ content they remember and what target language they are able to use.

6. Anticipating problems

All schools and TEFL programmes guide you to learn to anticipate what the problems of your students may be in order to prepare a “counter attack”. But anticipating problems can only be done before class, while preparing, by thinking about what might go wrong during the course of the specific activities you choose to do in class.

We could say that anticipation is a mix of patience, thorough observation and awareness. Students might have difficulties with: language transfer –L1 to L2 translation–, the structure of complex tenses, the uses of specific grammar points in context, the understanding and use of vocabulary words or expressions, and the pronunciation of these words or expressions, among many others; and it’s only through experience: knowledge of the target language you’re teaching, knowledge of students’ L1 and, most of all, knowledge of your students’ L2 proficiency that you will be able to anticipate possible difficulties.

So:

1) be patient,

2) build a database of difficulties your students have had during classes,

3) while preparing come up with easy and varied explanations of what you’re going to teach and

4) always ask yourself What will I do if… picturing as many scenarios you can think of; because being prepared for the worst will take you one step ahead of circumstances.

6.1 Specific conditions: Mixed ability classes and variable group sizes

A very common problem one comes across during in-company classes is mixed levels. There are times in which companies won’t pay for two or three different classes so once is forced to group all students in one or two levels when three or four would be ideal. The result? Mixed ability classes.

Mixed ability classes are not easy, but also not impossible. In a good mixed ability class one should offer all the students appropriate challenges to help them progress in their own terms. This means creating a context where all the learners have the space and confidence to try. In order to provide a range of challenges for different abilities, one would need a range of achievable objectives for many tasks, e.g. using five new words, saying one sentence correctly, or repeating an earlier exercise and getting it right. As an experienced teacher, you can set these small and achievable objectives on the spot by adapting activities to your specific students’ needs: maybe by asking weaker students easier questions, by giving them options to choose from, by acknowledging their effort even if their answer if not exactly right or by making turns predictable so they have more listening and thinking time before calling on them; but it’s never a bad idea to think, beforehand, of extension activities for stronger students and support activities for weaker students. Once we’ve decided we’ll use a specific activity for class we can always ask ourselves: how can I make this harder in case it’s too easy and how can I simplify it if it’s too difficult?

Another common situation we can prepare ourselves for, both while making activities and while preparing activities for a class, is variable group sizes. Sometimes you have a group of eight but only two show up, or you think it’ll be a one-to-one but a couple more students decide to join. There are a few exceptions to the “less is more” proverb; particularly when you have three pictures to distribute among six students. So, what do you do then?

Advantages and disadvantages of group and one-to-one classes aside, it’s good to have a plan B. Just in case. So the next time you come across the instruction of distributing pictures among students, pairing them up, asking them to take sides in a debate or assigning each a role, think about how you’ll sort out the scarcity or plethora of students so they all get enough practice of the target language and learning outcomes are met.